Most histories of China’s international trade and industrialization focus on the role of its coastal provinces: Guangdong, Fujian, and Shanghai and the nearby provinces Jiangsu and Zhejiang. Guanghzou (then called Canton) was one of the few designated ports open for foreign trade in the Qing dynasty under the Hong system. During the period of European colonial treaty ports, British-ruled Hong Kong and Shanghai were home to most of the advanced factories and technology in China. While its certainly true that China’s coastal and southern areas led the country in foreign trade and imports of foreign machinery, understanding of China’s early industrialization would still be incomplete without acknowledging state-led industrialization efforts in the late Qing and early Republic years. These efforts, most clearly championed by late Qing statesman Li Hongzhang and others, have been seen as a “failed modernization” by many historians. Unlike the Meiji restoration in Japan, last-ditch efforts by an otherwise ossified Qing imperial state could not prevent parts of China from falling to foreign powers, nor the eventual collapse of the dynasty in 1911.

I recently visited Baoding—the prefectural city southwest of Beijing that was once the provincial capital of Hebei (previously called zhili 直隶 during the Qing Dynasty—meaning “directly ruled”). The main tourist attraction here is the former residence of the Zhili Viceroy (Governor) 保定直隶总督署. The position had been set up in the early Qing and was always important for its role in defending the capital. In the late Qing, this position became important as a power base for several influential officials who sought to undertake state-led industrialization efforts. Most prominent among these are Zeng Guofan 曾国藩, the official who helped put down the Taiping Rebellion, who held the position from 1868-1870, and his successor Li Hongzhang 李鸿章, who held the position from 1870-1882, again 1884-1895, and a few other periods until his death in 1901. From his power base in Zhili, Li became the late Qing’s lead negotiator on foreign affairs and treaties—his role in signing China’s so-called unequal treaties such as the Treaty of Shimonoseki Japan is one reason he has sometimes been viewed unfavorably in Chinese histories. But Li also helped jumpstart a number of China’s early industries under the self-strengthening movement (sometimes called “Western affairs movement” or in Chinese yangwu yundong 洋务运动.

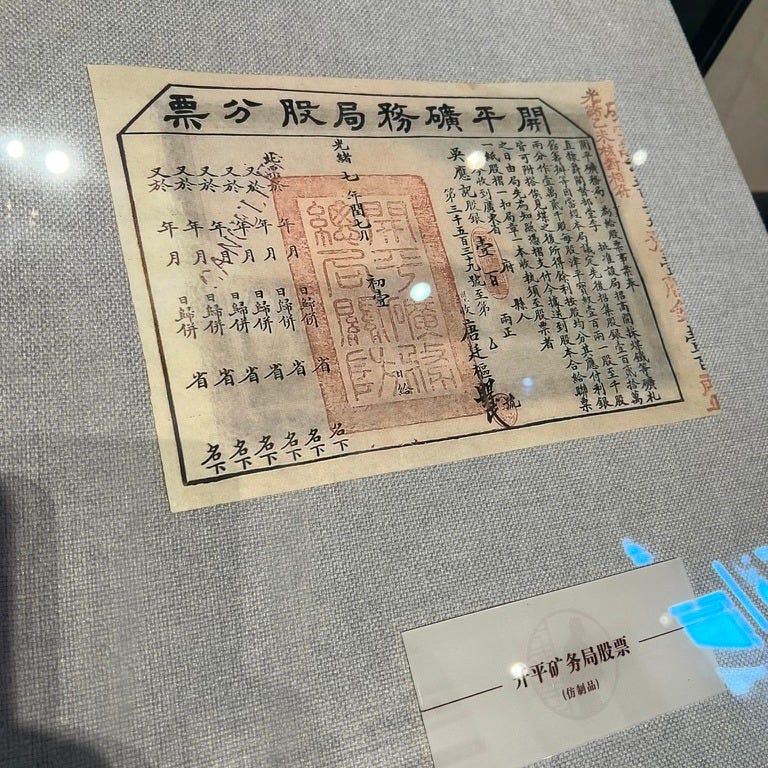

Li, through his concurrent position as “Beiyang Trade Minister”, was instrumental in setting up China’s first “state-owned enterprises”: the Kaiping Mines in what would eventually become Tangshan, China Merchants Steamship Navigation 招商局, China‘s Telegraph company, and China’s first self-financed railroads, which were built to connect the Port of Tianjin, the Kaiping mines 开平煤矿 (1881), and Peking.

Most of these early efforts were directly geared toward the rather limited goal of strengthening state governance and military modernization: coal was needed for factories to produce steel for modern ships and armaments. Railways were needed to transport coal from mines to factories, and could also transport troops. These efforts were not by and large aimed at stimulating a broader commercial revolution. In 1885 Li founded the Tianjin Military Academy 天津武備學堂 for Chinese army officers, with German advisers, as part of his military reforms. In 1902, Yuan Shikai, who held the Viceroy of Zhili and Beiyang Trade Minister posts, would found the Baoding Military Academy, which would serve as a key power base for Yuan during his brief reign as “emperor” in 1915.

Kuan Tu Shangpan 官屠商办 “Official Supervision Merchant Operated”

Despite the “failure” of Li’s modernization efforts, it would be wrong to completely neglect their deeper historical legacies and impact. Many of the companies Li founded played a major role in China’s industrial development—Kailuan Group (开滦集团) is the inheritor of the Kaiming mines. Today, China Merchants 招商局 is a major SOE employing 230,000+ people across 21 subsidiaries, involved in building numerous ports and other infrastructure around the world as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, and also owns numerous subsidiaries in real-estate development.In fact, the institutional arrangements Li deployed to run these enterprises can be seen as a forerunner of China’s state-planned economy in the Maoist years and the evolving state capitalist system under reform and opening.

The history of China Merchants Steamship Navigation in particular is the subject of Harvard East Asian monograph’s first book by Albert Feuerwerker. Originally founded in Shanghai 1872 as the China Merchants Steam Navigation Company, China Merchants, as most of these other companies, were set up as “government supervised, merchant operating.” Li, through his role as Viceroy of Zhili and head of the Beiyang Trade Minister, would be the official “sponsor” for these industries. Capital and investment was typically raised from merchants in addition to some government support—usually in the prosperous areas of Jiangnan, Fuzhou, and Canton.

Feuerwerker argues that the precedent for the operational structure of China Merchants was the system for imperial salt tax collection in the Qing Dynasty, essentially a tax-farming system of “official supervision and merchant sales” in which the government appointed official supervisors to manufacture, transport and sell salt, administered under provincial bureaus of the Ministry of Revenue. Certain merchants were essentially given monopolies on collection or distribution of salt in certain areas. As Fuerwuerker writes":

“from the past [the new industries] retained a bureaucratic management and the monopolistic restrictions and official exactions which had characterized the salt administration; these features were combined with such new nineteenth century developments as the growth of provincial at the expense of imperial power and the appearance of new sources of capital in the treaty ports. The product—the kuan tu Shang-pan institution—was deficient in the rationalized organization, functional specialization, and impersonal discipline associated with the development of modern industry in the West.”

The idea for a steamship company was to compete with the Western and Japanese steamships who had come to dominate coastal trade. The government would sponsor the company but most of the capital would be raised from Jiangnan merchants who would run the steamship services primarily between Tianjin and Shanghai, but also with lines to Hankou (Wuhan), and other coastal cities (Fuzhou, Amoy (Xiamen), and Hong Kong.

The Boon and Curse of Government Supervision

The CMSN Co was both a commercial enterprise and a government entity. The official patron (III., above) would be a government minister—first Li Hongzhang, and then Yuan Shikai, after him the Ministry of Posts and Communications “Policy matters were in the hands of the company’s official managers (II-B, above).” But at the same time, “the company was owned by its shareholders” (102-103). The relative degree of state oversight or lack thereof waned and waxed with the tumult of the late Qing—the ultimate end of the dynasty in 1911 led to a period in which CMSN operated basically as a commercial enterprise almost free of official supervision, until it was reassumed under the new Republic of China government.

As Feuerwerker notes, the quasi-official status of CMSN was both a boon and a bane, depending on various aspects. The company had a virtual monopoly on transport of government rice tribute and other products, which acted as a sort of subsidy. At the same time, official extraction of capital and resources could at times interfere with the operation of CMSN as a profitable enterprise, and some decisions were often made contrary to business interests of the firm. The company’s assets included its steam ships, as well as extensive real estate holdings mainly dock and warehouse space in Shanghai, Tianjin, Hankou (Wuhan), and smaller numbers in the other coastal cities it operated. Initial capital for the firm consisted of 110,000 tls (silver) raised from Shanghai merchants, 50,000 from Li Hongzhang personally, 135,000 from Zhili military funds” (124).

Implications for Understanding State Capital in the Xi Era

It would be tempting to see China Merchants and the early origins of Chinese state capitalism in the late Qing as a direct forerunner of contemporary state capitalism. Obviously that would be a gross simplification and skip over key details in the 150 or so years that have elapsed from the founding of China Merchants. Today, the Chinese state sector has far eclipsed the wildest hopes and dreams of Li Hongzhang to encompass some formidable companies that feature in the ranks of Forbes 500. While research has shown that SOEs in China are largely less innovative and deploy capital more inefficiently than private firms, they are important bulwarks of employment and agents used to pursue state economic and geopolitical goals such as Belt and Road, domestic infrastructure and urban development, and military technologies. Xi has indicated that rather than curtailing the power of the state sector, he views the state sector as crucial tools in China’s quest for technological self reliance and global leadership.

There have been periodic Party bromides over the years about SOE reform. In practice this has often meant mergers, centralization, and the creation of super firms while also maintaining forms of “managed competition” as Kyle Chan has written about China Railway. There have also been efforts to inject private capital through so-called mixed management or raising minority equity stakes in SOEs. But there are reasons this has proved less than popular for most private capitalists stems from some of contradictions and risks that are evident in China’s SOEs today, just as they were with “Official Supervision Merchant Operated” enterprises like China Merchants. Fuerwerker highlights the numerous times state management could jeapoardize business decisions of the more commercially oriented investors of the firm.

Xi Jinping, who has called for strengthening and modernizing state-owned enterprises, is again using the 京津冀 Jing-Jin-Ji region (formerly Zhili) as a base for his own efforts to boost state owned enterprises into engines for China’s push for indigenous innovation and self sufficiency in core technologies. Xi has family roots in Hebei-his mother’s side of the family originates from a county town not far from Baoding and his first government post was to the county of 正定 Zhengding, now under the administration of provincial capital Shijiazhuang.

This is the real potential of Xiong’an New Area (if it gets going)—which itself lies in three counties formerly administered by Baoding, and a short drive from the city. The removval of three counties from Baoding’ supervision can be seen as diminishing the city’s influence in the region at the expense of Xiong’an. But if the Xiong’an New Area does eventually take off (big if), Baoding could also benefit. Baoding has long been a manufacturing center through its large Great Wall Motors factory that is a large employer in the area.

Xiong’an could become home to a number of state-owned enterprises in renewable energy, infrastructure, power infrastructure, smart cities, and green building. Xi’s efforts to promote development around Beijing and Northern China comes after decades in which China’s Southern and Coastal regions led economic reform and opening, and became the wealthiest region of China, which they still are today.

Very interesting! Many thanks for writing it!

Baoding and Zhengding, two places I have visited (albeit briefly).