Khon Kaen, Thailand: local development amidst infrastructural geopolitics

China had designs on a maintenance facility in Khon Kaen as part of its effort to finance Southeast Asia's high-speed rail system. But local businessmen have already been making their own plans.

I’m standing on the rooftop viewing deck of the trendy Ad Lib Hotel in Khon Kaen looking over a sleek infiniti pool as the flat expanse of Thailand’s Isaan region stretches out toward the setting sun. Boutique handwoven textiles in colorful patterns line the walls of the new restaurant.

“You see, over there, just beyond the station is our plot of land,” says Suradech Taweesaengsakulthai, the CEO of Cho Tavee, a company that manufacturers flat bed trucks, and also the founder of Khon Kaen Think Tank (KKTT), one of Thailand’s first “city development corporations” or Borisat Meuang Pattana, a corporate entity set up by local businessmen to invest in local development projects.1

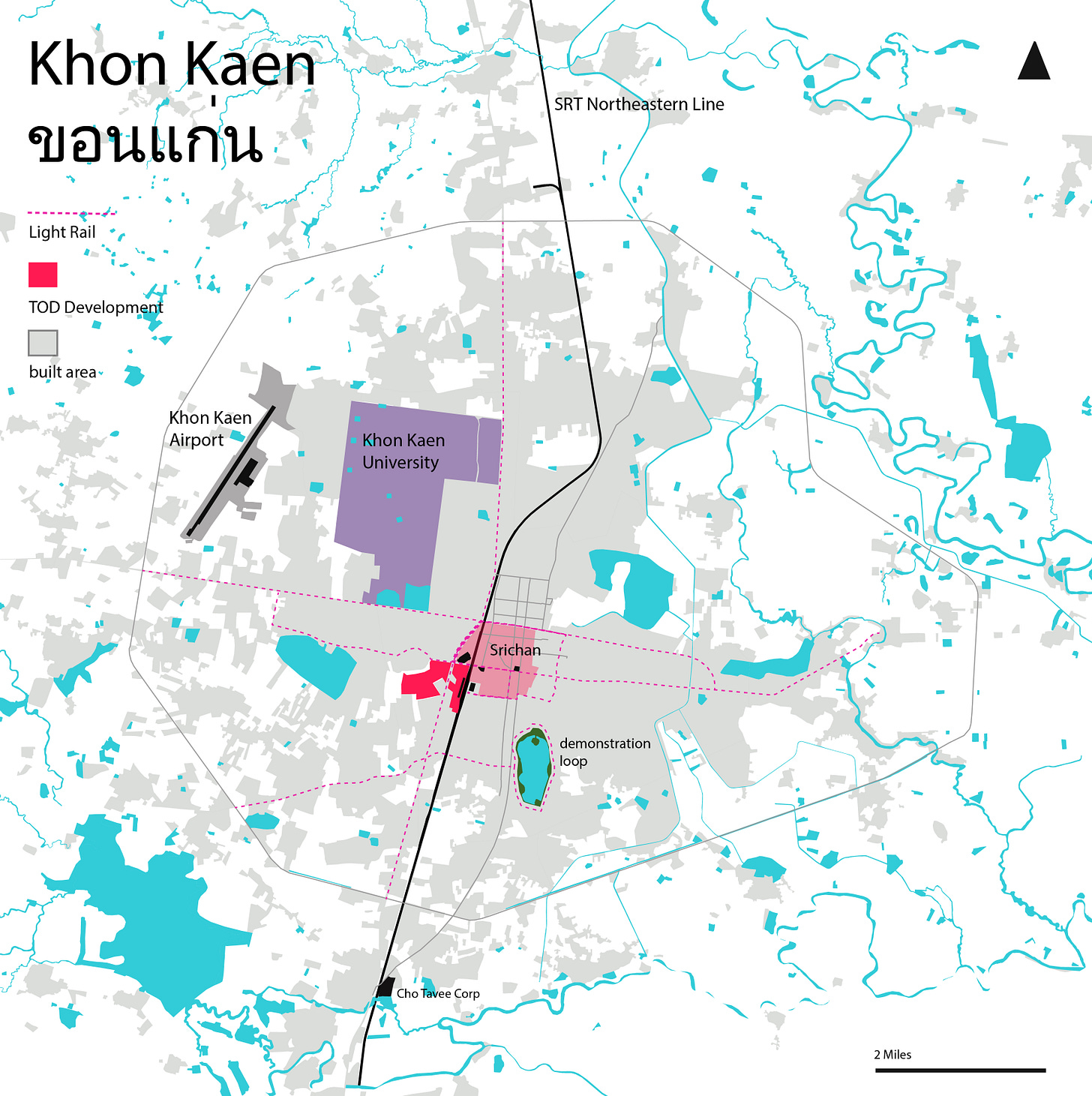

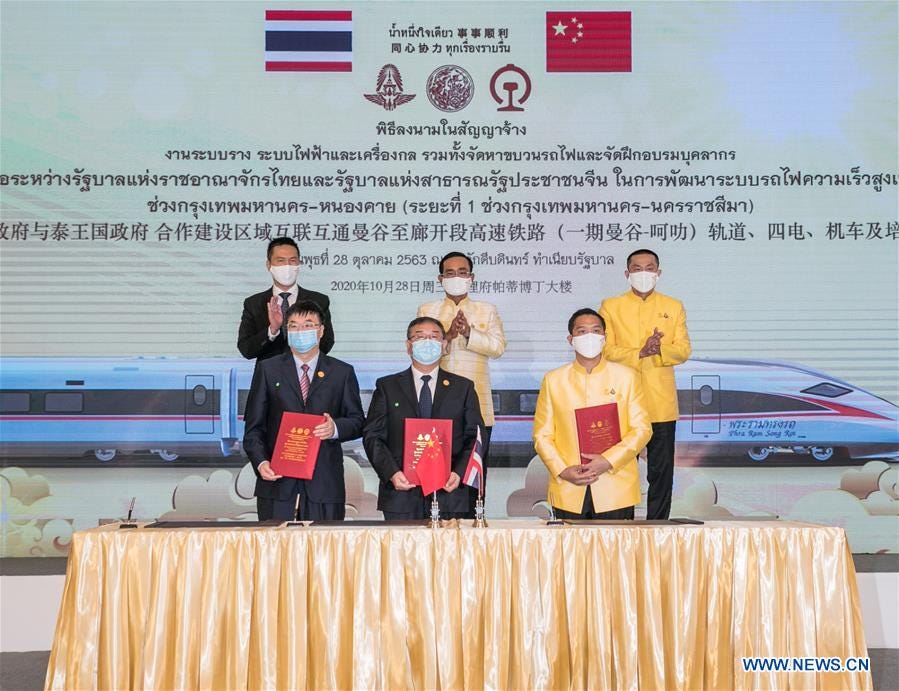

As the sun sets on water-filled rice paddies, a train groans into Khon Kaen’s small elevated station that was recently expanded in anticipation of a new “double track” line being built by Thailand’s State Railway Corporation (SRT). A passenger arriving in Khon Kaen from Bangkok might have left the capital just before 11 AM, completing the 8 hour journey just as the sun sets. Only three daily trains run along the Northeastern Line between Khon Kaen and Bangkok to the south, which was originally completed in 1930. Most of the carriages lack air conditioning and passengers stick their heads out of the windows to get a bit of a breeze. In December 2017, Thailand’s SRT embarked on the new elevated line from Bangkok to Korat (Nakhon Ratchasima), which lies about halfway to Khon Kaen. The second planned section which will cost 341.35 Bn Thb ($9.3 Bn), was just recently approved by SRT,2 and will eventually connect Khon Kaen to Nong Khai and the Laos border, where it would link up (sort of) with the China-financed high speed rail line already open in the small landlocked country. China has repeatedly pressured Thailand to pick up the pace of its stretch of the line, which has been hampered by bureaucratic obstacles and political instability over the years. In contrast to Laos, Thailand opted to finance and own the railway domestically, with China Rail Corporation as the technology vendor—giving Thailand greater leverage and agency in the projcet.3

While China’s rail aspirations for Southeast Asia are now increasing future opportunities for Khon Kaen’s development as a railway hub, the city of Khon Kaen itself owes much of its contemporary development to the investment in infrastructure during the 1960s, as the government led by military general Sarit with American military aid, poured resources into highways and military bases that would serve as a bulwark against the expansion of Communism from nearby Laos-then under rule of a Communist Party. During this period, Khon Kaen was envisioned as a hub of the Northeast for its position as a primary transshipment point from agricultural projects from the region down onto Bangkok.4

But for Suradech, the arrival of the high-speed rail is only part of his vision for Khon Kaen. In 2015 the businessman set up KKTT to help push for a city-led light rail system and transit-oriented development. In Thailand, local governments, especially cities outside Bangkok, are hamstrung by a centralized fiscal system that limits the ability of cities to fund infrastructure projects. The large rice paddy next to the train station is currently owned by the Ministry of Agriculture as an agricultural research station. But its prime location would make it valuable as the centerpiece of a planned citywide tram network that Suradech wants to build. The value from developing this parcel into a mixed-use commercial and residential area, along with a few other projects, would be used to fund the construction of the infrastructure, a classic land value capture approach.

There are a few snags in the plans of Suradech, who speaks passionately about the need to move beyond the limits of Thailand’s centralized administration. “If we don’t take a first step, we’re stuck on this escalator going nowhere,” he told me. While the national authorities have granted most of the necessary permits for Suradech’s plan, The Ministry of Agriculture has yet to relinquish the plot of land. “They’re doing things the Thai way,” he smiles, insinuating about improper but common requests for money to get things done.

But Suradech has not let these delays stop him. He’s flown to the U.S. to pitch listing a company of Thai city development corporations on NASDAQ to raise funds for local development in Thailand—a bold but perhaps unconventional move. He’s engaged the World Bank, German development organizations, Japanese and Chinese companies, on his quest to bring a modern transit system to Khon Kaen.

The next day, Suradech takes me out to Rajamangala University on the outskirts of Khon Kaen. He shows me a large factory-sized warehouse. Inside is an old brown tram, like something out of a Miyazaki anime film with Japanese kanji, from the city of Hiroshima. I’m a bit confused.

“Is this the tram you’re planning to bring to Khon Kaen?” I asked him.

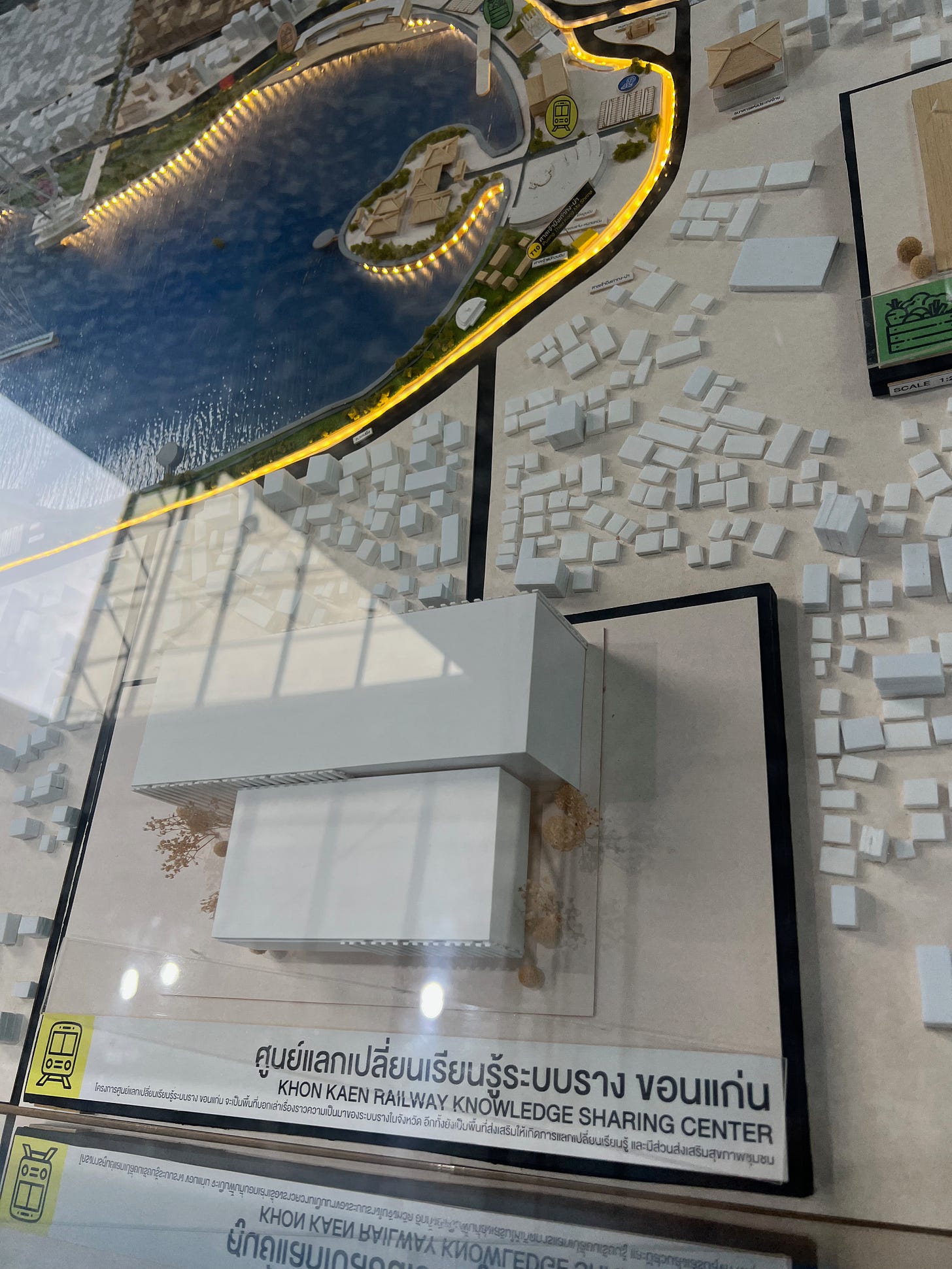

“No, no,” he explained. “This is for learning. We have had Japanese engineers come and teach local people the ‘philosophy of the tram’—maintenance, operations, safety. Then once we are ready we can develop our own local knowledge to build one ourselves. He explained how several years ago, Japan’s International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the overseas development assistance arm of Japan, offered to ship a decommissioned tram to Khon Kaen as part of a knowledge sharing project. The Thai government would not pay for the shipment. So Suradech paid for it and it shipped here to Khon Kaen.

“We’ve had German engineers come here, we’ve had some Chinese train companies come as well. We’ll learn from anybody,” he told me.

In Bangkok, a journalist I spoke to with knowledge of the SRT told me about the conflicts slowing down the construction of the Thai-Chinese railway line, the first section of which was being built from Bangkok to Korat.

“There is resistance at the working level, the Thai want to translate the manual, the Chinese aren’t complying. Thailand wants to do everything here, maintenance here. The Chinese want to do a big maintenance plant in Korat or Khon Kaen but it hasn’t taken off because of an argument about parts. China just wants a factory in the middle of Southeast Asia”5

“The Chinese are good at what they do but they maybe don’t know how to do with something here..Thailand has a system that works here, and not just works because the money but the workforce, the bureaucracy, things that make things tick. Chinese can’t just come in and expect things to work the way they do in China.”

Thailand’s rail line is still on track (pun intended of course) as of 2024, but it has proceeded more slowly and under State Railway of Thailand— different than in Laos which mostly lacked rail infrastructure before the opening of the 2021 line. The Laos China Railway (LCR) is a special company with majority Chinese ownership but based in Laos that operates the line.

The prospect of direct passenger service between Kunming and Bangkok remains a distant dream—and probably with little economic rationale for now. Budget flights can make the trip in a couple hours for around $100 one way. The benefits of the line will primarily be for freight and logistics. Already, new logistics parks are being built just 100 km north in Vientiane, for transfer of cargo between the standard-gauge of the Laos-China Railways and the narrow-gauge of the Thai-Laos railways, which is being extended from Nong Khai in Thailand across the border to the Laos capital Vientiane.

But the development of local light rail systems in Khon Kaen shows how local businessmen and elites in secondary cities in Thailand are mobilizing to pursue their own interests. While they are happy to receive Chinese technical assistance or parts if they need to, the effort to build a tram locally in Khon Kaen—if it succeeds, will be a first for Thailand, and a first for a city of the size of Khon Kaen.

Local Knowledge: Building a Light Rail System

Khon Kaen’s plans for city development began back in 2015, predating the announcement of the China-supported rail project, announced in 2016 as part of the new post-coup government of Prayut Chan-Ocha that unveiled a host of policies designed to boost the economy, including Thailand 4.0 and the Eastern Economic Corridor. In 2015, businessmen based in the city, led by Mr. Suradech, founded KKTT as a “city development company” or borisat pattana meaung. The entity is set up as a private company with investment from the various businessmen, but with a mandate to develop public infrastructure for the city. In 2017, Khon Kaen City Municipality set up a company to own and operate a light rail system, with 20% minority investment from the surrounding cities under Khon Kaen province.

As Suradech tells me, “this is the first tram in Thailand that would be locally built and has local content more than 80%, all the systems and university suppliers, they try to do research together, so it is about technology transfer learned from China also—Liuzhou, Jiaotong University, Lanzhou, Beijing railway universities, we went to see European examples too. This tram looks like the Siemens one because we think it looks nice. This tram combines some Japanese influence too (not for technology but for the philosophy of the tram—how to operate, how to fix the tram, safety)…so we know the basic of the tram and for building our own tram we select many technologies around the world.” City elites in Khon Kaen are struggling not against foreign powers but against the sluggish bureaucracy and entrenched inequalities in Thailand’s Bangkok-centered political economy.

The Khon Kaen plan also represents the common strategy of elites using infrastructure projects for land-value capture. Suradech’s own CTV Company stands to benefit from building the tram locally. As a Thai consultant with the World Bank who is also from Khon Kaen tells me, “For Khon Kaen, the people who are rich and powerful there they have to rely on value capture, Rayong is the same. There is element of rich and powerful people have to be there. In Chiang Mai most of them sell their land or stay in Bangkok.”

If local business elites are invested enough in their city, they will also be motivated to invest in public goods—at least that’s the thinking behind KKTT. Over the past few decades, Suradech and other businessmen in KKTT have forged longstanding working relationships—with city leaders, academics, foreign technology vendors, and government agencies. A friend of Suradech, a professor of urban planning at Khon Kaen University tells me, “the Khon Kaen model is not the TOD or train project, its the relationships we’ve built up over twenty years. We just keep talking to each other and get things done.” If KKTT and Cho are able to develop a tram locally, this would bring benefits for the city not only from the project itself but also in jobs from building the system and acquiring technical and operational knowledge. Later in my visit I’m taken to meet with the local branch of Thailand’s Creative Economy Agency (CEA), which was instrumental in developing Bangkok’s creative district along Charoen Krung road. Now they’ve opened branches in secondary cities (including Songkhla in the South, and Khon Kaen) to develop local crafts and artisanal industries. They’re working to develop the downtown Srichan district into a creative district—the downtown area at the heart of the planned light rail system. In another discussion with members of the Khon Kaen Think Tank, members talk about plans for boosting molam, a local performance tradition to attract tourism, and an idea for digital currencies and metaverse projects. 6Some of these may develop further and some might just be grabbing at the latest buzzwords.

City Development in Thailand: Local Interests, Domestic Politics, Global Connections

As of early 2024, the first trial line of the tram system was expected to begin in 2025.7 Whether or not this will proceed depends on the approval and support Khon Kaen can obtain from the central government. For Khon Kaen, China’s assistance with Thailand’s railways could be an additional factor but it is not the primary driving force for Khon Kaen’s light rail or related TOD plans. This is primarily being driven by local businessmen in tandem with local officials and academics in Khon Kaen. The longstanding inequality between Northeastern Thailand and Central Thailand has been a persistent source of tension (and a factor in the rise of Thaksin and two coups in 2006 and 2014 followed by 9 years of military rule under Prayut. With a tenuous coalition in Thailand between Pheu-Thai (historically strong in the NE) and conservative/Royalist factions, Khon Kaen could be in a better political position to receive favorable policies from the central government. Whereas China wanted to open a rail maintenance facility in Khon Kaen for high-speed rail, Khon Kaen has pursued its own policy of “local capacity development” through training local residents and students how to build and operate a tram locally, bringing in expertise and knowledge from Japan, Germany, and yes Chinese companies too. But there is still an uphill battle for this small secondary city to embark on the development plan its boosters envision. If it does, it will be a model of local development for Thailand and for secondary cities elsewhere.

Similar entities have been set up in Rayong, Phuket, Chiang Mai, and over 20 other Thai municipalities.

https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2780144/2nd-phase-of-thai-china-rail-gets-nod

The State Railway of Thailand (SRT) board has approved the second phase of the Thai-Chinese high-speed train project from Nakhon Ratchasima to Nong Khai with a total investment of

Please credit and share this article with others using this link: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2780144/2nd-phase-of-thai-china-rail-gets-nod. View our policies at http://goo.gl/9HgTd and http://goo.gl/ou6Ip. © Bangkok Post PCL. All rights reserved.

See also: Lampton, David M., Selina Ho, and Cheng-Chwee Kuik. Rivers of Iron: Railroads and Chinese Power in Southeast Asia. First edition. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2020.

Ouyyanont, Porphant. 2017. A Regional Economic History of Thailand. ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute., pg 329

Conversations at the Thai Foreign Correspondents Association, 2022, 2023

“KKU launches “Molam Metaverse”, the cultural capital innovation that experiments on touring of the virtual world and upgrades Isan Molam towards the digital world” https://eng.kku.ac.th/16432

https://www.nationthailand.com/thailand/general/40036060