CITY REPORT: The "Datong model" of heritage reconstruction 10 years later.

In 2024, Mayor Geng Yanbo's vision for reconstructing the old city of Datong has nearly come to fruition. Was it worth it?

This summer I visited Datong 大同 in Northern Shanxi 山西 province. When I was living in Beijing 10 years ago, I had heard of how the city was being remade into an ersatz simulacrum of a historic town through reconstruction of its city wall. But I had only been to Pingyao 平遥, a city with a (still preserved, not fake) old city wall that had already become a tourist attraction. Back in Beijing in 2024 I was glancing at my Xiaohongshu— I saw a lot of young individual tourists were visiting historic temples and cities across Shanxi province. This was a far cry from the early 2010s when these places were mostly sleepy towns, with a nascent tourism industry geared at foreigners, domestic group tours, and a few well to do Chinese who stayed at boutique hotels. I decided it was finally time to check out Datong.

I traveled to Datong with a friend of mine who works in the travel department of a large Chinese tech firm, so he quickly found and booked a new chic-looking hotel called Tongshe 同舍. The best part of the hotel was its beautiful lobby with a panoramic glass view of the Huayan Temple 华严寺. There was some neglect of finer details such as when a shower flooded and the AC didn’t work properly—but I digress.

Datong and its environs has a wealth of heritage. The city was the capital of the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏 (386 to 535), a time when Buddhism was being disseminated throughout China. The most famous site is the Yungang Grottoes 云冈石窟 which has 252 caves and 51,000 statues. I had a hazy recollection of visiting the grottoes (but not the city of Datong) in 2009 as an exchange student in Beijing when there were very few tourists. We had completely bypassed the city of Datong as it was known for being a polluted industrial town thick with coal smoke. This was before the city’s walls were totally rebuilt by Mayor Geng Yanbo 耿彦波, which required displacing 500,000 residents (and demolishing 200,000 homes).

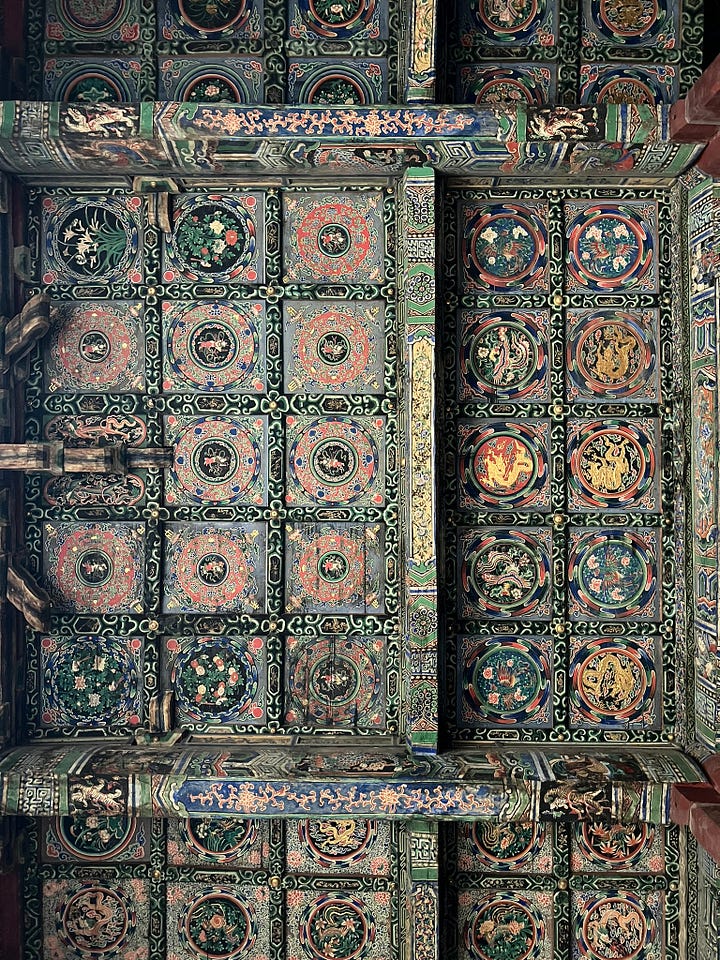

On a beautifully crisp August day in 2024, there were thousands of people lining up to get inside some of the more popular caves built into the hillside an hour Northwest of the city of Datong. But it was worth it to gaze up at Buddhas several stories tall and remark on the skill, effort that led to these artistic creations and remarkable good fortune that they are still preserved. There are also two beautiful old temples in Datong that we visited—the famous Huayan Temple, with statues and art dating from the Northern Wei and the Liao and Jin dynasties (907–1234) and the Shanhua Temple 善化寺, founded in the Tang dynasty.

Back in Datong City we wondered the remade “ancient” streets of the city, my friend and I trying to guess which buildings were ‘real’ and which ones were fake-or rather “rebuilt.” The safe answer was that most structures were rebuilt besides the temples and a few other sites. Certain elements have a somewhat tacky ‘Imperial Chinese Disneyland” vibe. The city wall is impressive, but the southern forecourt or barbican (main entrance to the city wall) is surrounded by a large park which gives it the feeling of a city preserved as a museum, separated from the modern city which has been built around it.

The shopping arcade features somewhat whimsical elevated pedestrian bridges, and a quick glance behind the shopping street reveals the “back stage” of normal drab old buildings that were covered to give the appearance of an old city—literally a face engineering project or 面子工程. One of the reconstructed sites, Prince Dai Palace, is a minitature Forbidden City that hosts a nightly light show tianxia datong 天下大同. In the Yongle Emperor of the Ming, Datong was made a Western outpost for one of the princes of the royal household to protect Beijing’s Western flank. Now the show features somewhat cringey performers dressed in mock ethnic dress of Thai and Central Asian peoples—indeed the city’s name Datong comes from the Confucian notion of the world in peace and harmony “great harmony under heaven” or Datong. The show depicts many races and people’s coming to pay tribute to the court. Is this a not so subtle nod to Xi’s “Community of common destiny for mankind.”?

Back in the early 2010s, the reconstruction of Datong’s city wall was a big focus of Mayor Geng Yanbo’s plan to reconstruct the city of Datong as a way to boost the city’s economic development. It was also the focus of a 2016 documentary The Chinese Mayor. A friend of mine had mentioned that there was this documentary, and upon returning to the U.S. I watched it. The film is a remarkably unfiltered view of the Chinese governance system at the local level. I was amazed that the filmmaker obtained such access. At the end of the film, Mayor Geng—who has been suddenly reassigned to the provincial capital Taiyuan, remarks somewhat comically, “I hope I wasn’t too fierce in your recordings—what did you actually shoot? I totally forgot about your existence during this time.” That might not be so surprising as the Mayor routinely woke at 4 am to start work, angering his wife, and revealing his dedication and hard work to transform the city. Mayor Geng’s plans were not met with total welcome. The documentary shows the numerous residents who suffered violence, removal from their homes, and were delayed in obtaining relocation homes.

The documentary provides a raw and mostly un-editorialized view of Mayor Geng and his efforts to transform Datong, but the indeterminancy of the film lets the view decide whether they think the Mayor’s actions were worth it. On the one hand, Mayor Geng’s unflinching criticism of his underlings, his unsmiling comportion, and his lack of concern with the thousands of families required to move for his project make for a rather unflattering portrait. But Mayor Geng believes rebuilding Datong’s wall and other sites will “give it a splendid future.” When the filmmaker asks Mayor Geng why can’t his approach be a bit softer, he remarks, “How long will I stay in Datong, the city has to seize this opportunity, if it misses out it won’t come again.”At the end of the film shows citizens lining the streets calling for Mayor Geng to return on the eve of his sudden departure to Taiyuan. An earlier scene shows a petitioner asking Mayor Geng for a better relocation compensation, but remarks, “to be honest, you are the first good Mayor we’ve had in Datong.” The Mayor meets openly with citizens who ask him for better terms, or to look into their case. His open and direct style wins him trust , despite the hardships caused for many.

The dusty streets and dingzihu (nail houses of those who refused to move until the last minute of demolition) shown in the documentary are a far cry from the polished restored ancient streets we walked in 2024. And yet, from the top of the pagoda of Huayan Temple, we could glimpse a few swathes of the city (mostly 5-6 storey residential flats) still waiting to be demolished so the old city’s reconstruction can be complete. Beyond the wall are high-rise apartments ringing the old city —an even taller wall beyond the one Mayor Geng rebuilt. As we depart from the high-speed Train station, empty high rises line the roads—the cab driver tells us many are not fully occupied—a common sight across Chinese cities during the real estate downturn.

But the city was no longer polluted—the air had once been thick with coal smoke as a leading coal producer and one of the most polluted in the country. The city was attracting tourists. But there was indeed something unsettling about this approach to historic reconstruction. It’s true, like Mayor Geng, if Datong had not seized the opportunity the city may have indeed have missed it. Although, as Mayor he was also reacting to the unique constraints and standards of performance used to evaluate political performance and as such promotion to higher posts. Mayor Geng served in Taiyuan but then retired in 2019.

China’s period of rapid growth had provided a window of opportunity for massive demolition and reconstruction that today would probably be unfeasible (except for Xiong’an, that is). On the other hand, this method of historic reconstruction seemed to forget about people as the essential element of culture. The obsession with reconstructing old walls and streets overshadowed an appreciation for people as living heritage. And the reconstruction of Datong has been criticized for its lack of authenticity and sloppy reconstruction.

On the one hand, as scholars of heritage have remarked, there are different attitudes towards historic preservation in Asia. The fact that most temples are made of wood means structures have to be replenished and rebuilt constantly—buildings are living objects. This contrasts with a Western view where preserving the original materials is often seen as an important aspect of authenticity—think ruins of the Roman Forum or Coloseum. They are (mostly) left as they were, not rebuilt into a gleaming new Forum. Japan is an apt comparison—its wooden temples also require constant rebuilding. But in Japan, historic towns like Kyoto don’t feel quite so fake or so Disneyfied as places like Datong.

The method of preservation in Datong and some other Chinese cities (like Wuzhen, the theme-Parkified water town outside Shanghai) is a direct reflection of China’s land and property system where the state owns all urban land. Some residents in the documentary express frustration as they are told by bureaucrats their homes were technically illegal when they were built and thus they can’t get compensation. “Why should I pay the price when it’s the government who was wrong then?” one angry resident asks. The state can provide new houses, but it can never really provide security of land tenure when land is considered a national asset. This allows Mayor Geng to do that kind of wholesale reconstruction he embarks on. But it also means the connection of individuals to the land is precarious. How much “urban culture” can one talk about in this context? This is a question that Chinese cities will inevitably face, particularly as there is the widespread recognition and complaint that Chinese cities increasingly look all alike.

…More on this aspect, in a subsequent post!

Out of curiosity, did they also build new housing stock in the old town? What separates redevelopment from Disneyland, in my opinion, is whether people are actually living there.

Caught By the Tides brought me here — phenomenal read. Any thoughts on the film, if you’ve seen it?