China’s Data Center Boom: a view from Zhangjiakou

After a quick 40 min high speed rail trip from Beijing North Station, I step off the platform in the sleepy station of Donghuayuan Bei in Hebei’s Zhangjiakou. From the elevated platform I get a glimpse of the wind turbines dotting Guanting Reservoir 官厅水库. On the other side of the platform I look out across a semi-rural landscape, dotted with apartment blocks and in the distance the hulking warehouses housing new servers to power China’s computing needs. The reservoir was built in the 1950s to provide Beijing with water. In the lead up to the Winter Olympics in 2022, Zhangjiakou saw a boom in infrastructure investment, including in renewable power, much of it to supply Beijing. Now, the city is being mobilized to supply the capital again, this time with its growing cloud computing infrastructure.

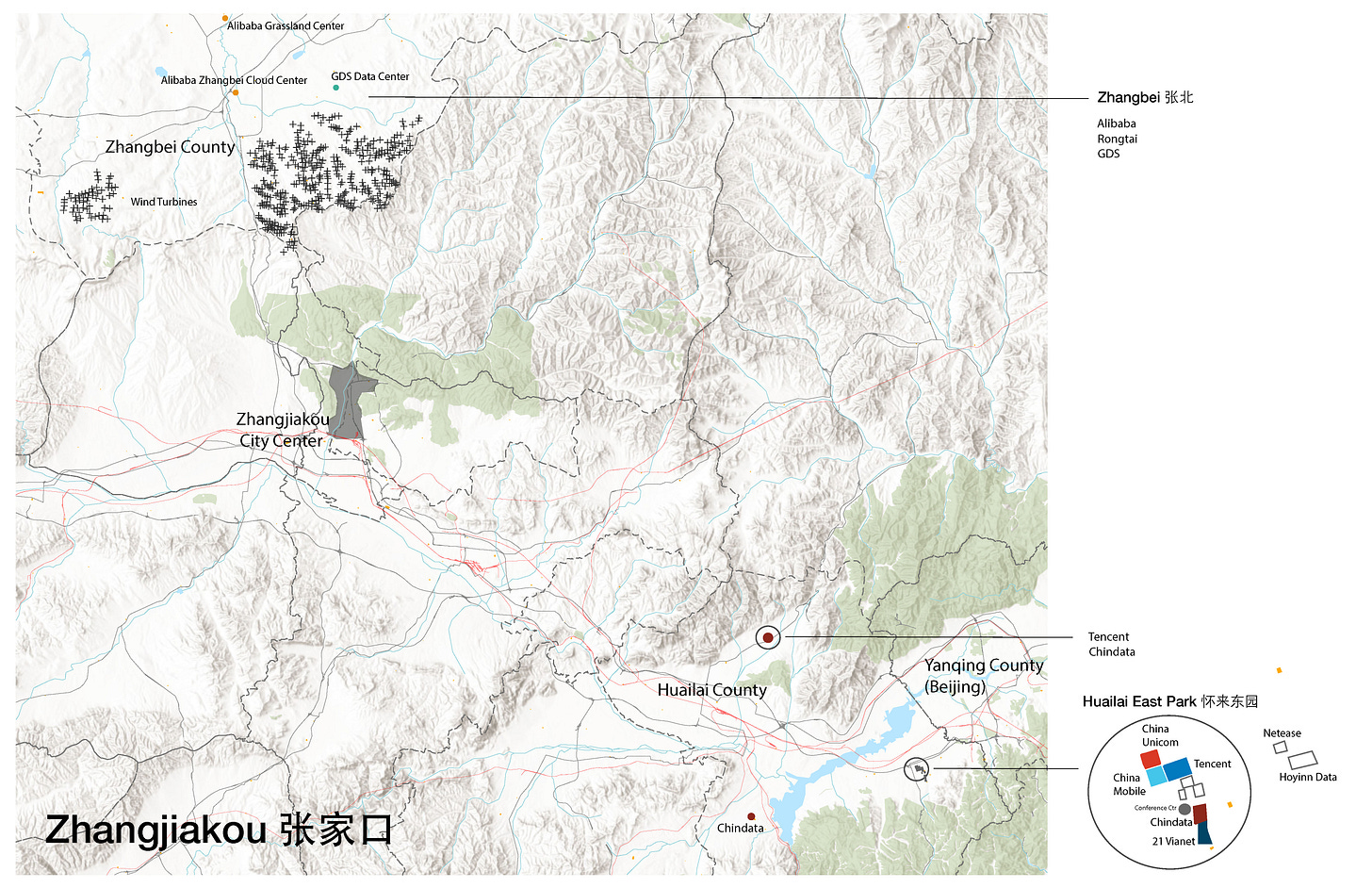

This is one of the eight data center clusters数据中心集群 of China’s Eastern Data Western Compute dongshu xisuan 东数西算 project. In this post, I’ll touch on some of the dynamics of China’s AI infrastructure and data center development through Zhangjiakou. Why this city of all the eight clusters? Zhangjiakou is adjacent to Beijing, and therefore offers lower latency for cloud//AI usage than more remote clusters, and also has solar and wind energy. This is why Zhangjiakou is attracting significant private data center investment in addition to those of state-operated telecoms, making it a relative success compared to some of the other more far-flung clusters such as in Gansu and Ningxia, or those in Xinjiang (which are not officially part of the EDWC plan).

The EDWC project was conceived to coordinate the growing energy needs of data centers with renewable energy buildout. However, the process of data center and energy permitting has turned into a new arena of political contestation. Some data center operators bribe their way to obtain permits for building from local governments, fueling a speculative boom that may outstrip the capacity of renewable energy in the areas where they are built. Even as data centers are built adjacent to renewable sources, they actually draw heavily on dirty energy like coal or gas-fired power plants, which provide a more reliable energy source required by data centers. According to a recent report from Xinhua , Zhangjiakou’s data centers used 1.859 billion kWh, up 43.47% YoY—-”green electricity” accounted for 574 million kWh, about 30%.1

By some measures the effort has been a success—according to official statistics released by China’s National Data Bureau 45.5 bn Yuan ($6bn) of capital has been invested in data centers via the plan.2 However, other reports suggest that many data centers lie underutilized or even empty. When the effort was conceived, the idea was to “optimize the layout of China’s data centers.” The plan sought to avoid overbuilding of data centers in crowded urban areas where land and energy prices are higher and concentrate data centers where there was ample cheap and renewable power supply. But in fact, the EDWC policy has encouraged many cities beyond the eight official clusters to pursue data center development. Real estate companies and other conglomerates have tried to grab a piece of the data center building frenzy, leading to creation of companies that have little experience in data center buildout. The result is a familiar story of overbuilding and overcapacity—time will tell if data center demand will catch up with the overinvestment, or if the frenzy will end similarly to China’s real estate boom, with empty and/or underutilized facilities.

In 2022, four agencies jointly issued a plan called Eastern Data Western Compute 东数西算, which aimed to boost China’s computing power by constructing new data centers in eight designated clusters across the country.3 China’s western provinces are rich in energy: both traditional oil and natural gas, as well as renewables like wind and solar. Meanwhile, most data centers had been built in the prosperous eastern metropolises, to be nearer to most customers. Latency, a measure of the time it takes for a packet of data to travel between a user and the server and back, is highly correlated with distance: closer computing facilities enable lower latency, and faster computing. But the western hubs would be suitable for certain data operations: cold storage and backup. With the advent of energy-intensive AI model training in the wake of ChatGPT’s release, suddenly inland data hubs had a newfound purpose as ideal sites for intensive model training operations. As many of you know, I’ve been covering the EDWC policy for a while, but this year many English language outlets began to pay attention—writing about newly built data centers in Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Wuhu—which the FT called “China’s Stargate”, alluding to the massive OpenAI backed data center being built in Abilene Texas.

The EDWC plan built on the initial success of Guizhou, which began attracting data centers by major Chinese tech companies around 2013, and later Inner Mongolia, which sought to replicate Guizhou in the North. Both inland regions are blessed with suitable cooler climates, and energy: Guizhou with hydropower, and Inner Mongolia with wind and solar. In 2022, the EDWC plan was released, adding six additional clusters to a national framework. Four of these (Shaoguan, north of Guangzhou; Wuhu West of Shanghai, Zhangjiakou outside Beijing; and Chengdu-Chongqing) are located in or near major metropolitan areas, while four of them were in remote Western regions: Qinyang in Gansu, Hohhot (Inner Mongolia), Guizhou, and Ningxia.

Meanwhile, many cities outside these began building data centers. Datong is a city in northern Shanxi province, just southwest of Zhangjiakou. While no cities in Shanxi 山西 province are part of the official EDWC plan, the province’s climate, location, and cheaper land and energy costs make it an ideal location for data centers like its larger neighbor to the north, Inner Mongolia. Chindata, a leading Beijing-based data center operator, built a massive hyperscale facility in Datong. Other cities in Inner Mongolia have cultivated their own data clusters. Ulanqaab 乌兰察布is a prefecture-level city in Inner Mongolia, located about halfway between the provincial capital Hohhot and Hebei’s Zhangjiakou. It has developed a big data industrial park with large cloud computing facilities, including Apple’s second data center in China. Even within Inner Mongolia, the rise of two cloud computing hubs is indicative of the decentralized rollout of data center development, seen by local governments as a new engine of growth. Specialized data centers in Xinjiang and Tibet have also attracted media attention recently. While these regions have high solar and wind potential, their distance from urban areas makes them relatively unattractive for most types of data centers, but they could be used to train AI models, which does not require lower latency needed for real time computing.4 Desert data centers in remote Yiwu, Xinjiang got attention from Bloomberg earlier this year, but in reality China’s data center boom is mostly still happening in areas closer to major cities—in places like Zhangjiakou 张家口which offers both proximity to Beijing, and benefits of cooler climate and abundant renewable energy. Getting trained engineers and reliable infrastructure to operate data centers in Inner Mongolia and Gansu is hard enough, let alone in remote Xinjiang.

Data centers are promoted as drivers of digital industry and remedies for the “digital divide” in the underdeveloped and poorer areas in which they are being built. However, the construction of data centers offers few of the benefits of productive industries such as factories. There are few jobs and because data centers don’t directly produce anything, they don’t offer much in the way of stable tax revenues for local governments. They don’t lead to many spillover industries, as the main beneficiaries are users located in main urban areas. Local governments have given land subsidies and tax breaks for data center construction, with little to show for it in return.

Securing Energy and Water

Some municipalities can generate revenue by selling credits for renewable energy supply used to power data centers. In the case of Zhangjiakou, I was told by a researcher who had met with local officials there, that they city was essentially selling quotas for wind power (风电指) to generate revenue to pay down the city’s debt, which had accumulated from years of overinvestment following the 2022 Winter Olympics. “The city is essentially mortgaging its future,” he told me. “The city has to use the revenue to pay down its existing debt, and doesn’t get much benefit from the data centers directly.” The city can sell its credits to energy operators, which build the renewable power that is being used to justify the data center boom. The wind power quotes are based on a city’s wind power potential, so Zhangjiakou was allotted a higher amount.

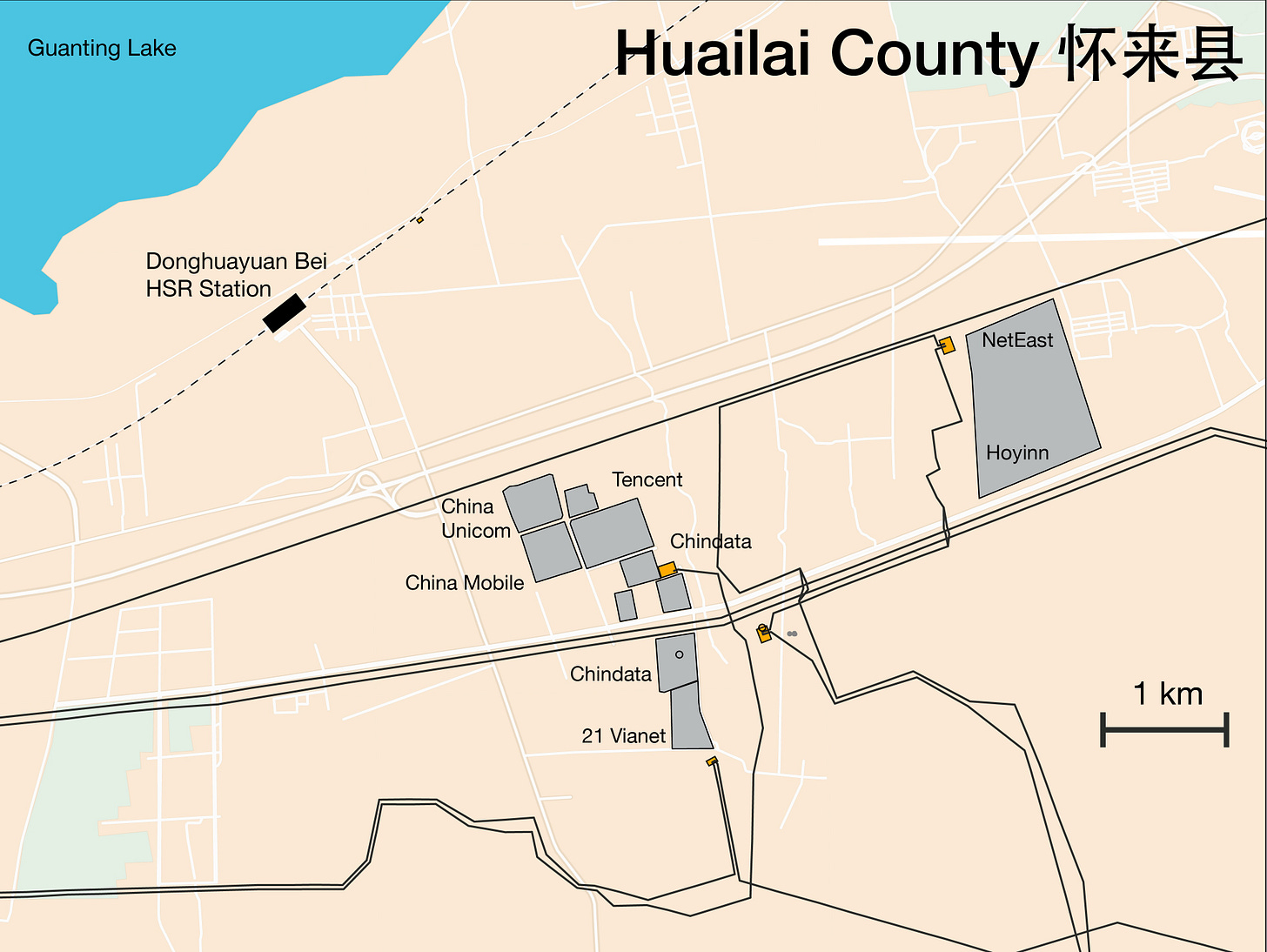

Huailai County怀来县 is ground zero for Zhangjiakou’s data center boom. Adjacent to Beijing’s Yanqing County 延庆县, home to the famous Badaling section of the Great Wall, Huailai has an ideal climate for data centers (and wine grapes, as well). Proximity to Beijing offers low latency for real-time computing needs. The 2022 Winter Olympics, which were mostly hosted in Zhangjiakou, resulted in a boom of investment in infrastructure and housing. Like many cities in China, Zhangjiakou is heavily in debt. New housing flats constructed a few years ago are mostly empty, some of them purchased by Beijing residents looking for a cheap place to retire or visit in the summers, when the area is cooler than the capital. Wind turbines blanket the area, some of them dotting the shores of Guanting Lake, a large reservoir. But a local tells me these projects mostly pre-dated the data centers and provide energy to Beijing. “There hasn’t been much economic impact from the data centers. They employ some local people, but mostly in lower jobs—technician or security guards. Most of the engineers are college graduates from elsewhere, or Beijing. A high-speed rail station near the area is just a 40 min train ride to Qinghe Station, in Beijing’s Haidian District-where the country’s top universities and an important tech industry cluster is located.

Data centers consume huge amounts of electricity. The approval of data centers is supposed to be conditional on the securing of power supply from the local grid. According to one person I spoke with, a family friend in Baoding (a city in Hebei just southwest of Beijing) was trying to bribe their way into securing a permit for a new data center, but was still unable to get approval for the energy permitting. The local branch of the NDRC (发改委) is supposed to approve data center construction in each municipality. In July of this year, Xi gave a speech earlier this year where he cautioned against cities rushing to build data centers.5 So there is official recognition that the data center buildout may have gotten ahead of itself.

The EDWC plan was premised on the securing of renewable energy supply. In practice, however, many of the data center hubs’ energy needs exceed that offered by renewable power. Even in Zhangjiakou, a hub for wind and solar energy, the data center draws only part of its supply from wind and solar. Much of it comes from a coal-burning steam-powered turbine facility in the county of Xuanhua, operated by central SOE Datang Group.6 In Hohhot’s data center cluster south of the city, a new steam-turbine power station was built by a Beijing-based power company near the cluster to secure supply.7 Wind and solar do not yet provide the constant reliable power that data centers require. Until improvements in battery storage or efficiency, the promise of green data centers may be more “greenwashing” than reality, as data centers suck up power that requires stable if dirtier sources as coal and natural gas.

Water is also required to cool data centers. The Zhangjiakou data cluster is in an arid region, although the Huailai cluster is close to the Guanting Reservoir. But according to conversations with villagers in the area, water used to cool data centers has to be sourced from groundwater, not the reservoir. This means the cooling demands of data centers could exacerbate groundwater depletion, which is already a significant issue in North China.8

Different Types of Data Center Operators

Unsurprisingly, much of the investment in the EDWC computing hubs has been from the three major state-owned Telecoms (China Telecom, China Mobile, and China Unicom)—see my figure from data compiled in 2024. But there are two other main categories of data center operators building data centers: some are built by i.) leading cloud companies (Ali Cloud, Tencent, and Baidu), and many by ii.) third- party data center operators that lease their space to smaller companies (called the “co-location” model)—such as Chindata 秦淮数据, 21 Vianet 世纪互联, and Shanghai-based GDS 万国数据. ZData (中联数据) is another growing third party data center operator with a new center in Hualai County as well as in Shanxi province.

These companies are now expanding abroad and have to carefully balance maintaining their China businesses and good relations with the government while expanding abroad—which often requires them to hide their connections to China state entities or create new entities. For example, Chindata, whose largest shareholder is Bain Capital, restructured itself. A holding company based in the Cayman Islands since 2018 owns some of its overseas investments such as Bridge Data Centers, which has been building in Malaysia.

Their Beijing-based subsidiary oversees its China projects, most of which are in Northern China. GDS, which is partially backed by Shanghai’s Zhanjiang high Tech Park, but also owned through a Cayman Islands holding company, has pursued a similar strategy as it expands overseas with new data centers in Malaysia and Singapore. GDS has also evolved from being a mere data center operator to an advanced AI infrastructure provider.

The EDWC boom has drawn in a new cohort of data-center operators beyond the telecom SOEs and established cloud platforms. These are often started as by real estate developers or other conglomerates that have little experience building data centers but are trying to get a piece of the cake. For example, one of the largest data center facilities in Zhangjiakou (a planned 1000 Mw “data industrial park”) is being built by a company called Hoyinn 合盈 The company is majority owned as a subsidiary of the Tianjin-based Zhengxin Group 正信集团, which has primarily been a residential real estate developer.9 Beijing-based Haoyang Group, began in 2021 as a relatively small player with a data center in Langfang, located between Beijing and Tianjin, and is now building a hyperscale facility in Thailand.10 The Chairman of Haoyang, Lai Ningning (赖宁宁), founded CNIX, an internet exchange company in 2016. The company is partly backed by U.S-based Apollo Capital.

Conclusions

Zhangjiakou’s data center cluster is already one of the more developed among the eight—and because of its proximity to Beijing and favorable energy potential, offers an ideal mix of conditions for data centers. But even in Zhangjiakou, data centers have, like elsewhere, failed to deliver significant economic growth. The city remains highly indebted due to years of excess infrastructure buildout both leading up to and following the 2022 Winter Olympics. The dynamics of energy policy and corporate investment in Zhangjiakou are themes that can be seen in China’s broader data center buildout, which has already led many observers and even Xi himself to caution against the rush towards data centers by local governments. But for now, there seems to be no sign of a slowdown…

http://www.news.cn/local/20250416/fc2ae024ed40480ea3f681b791ab0a74/c.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

For comparison, U.S. data center spending was estimated at 15bn and expected to be 60 bn in 2025, far exceeding the official number quoted for the EDWC.

These are the Ministry of Information and Industry Technology (MIIT), National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), National Energy Bureau (under NDRC), and the State Council

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-07-08/china-builds-ai-dreams-with-giant-data-centers-in-the-desert

https://www.ft.com/content/9c19d26f-57b3-4754-ac20-eeb627e8723e

https://www.gem.wiki/Zhangjiakou_power_station

内蒙古京能盛乐热电有限公司

Michele Lancia et al. The China groundwater crisis: A mechanistic analysis with implications for global sustainability, Sustainable Horizons, Volume 4, 2022, 100042,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.horiz.2022.100042

http://www.zhengxingroup.com/aboutus/#

https://www.forbes.com/sites/iansayson/2025/06/13/beijing-haoyang-to-build-22-billion-data-center-at-wha-site-in-thailand/