CITY REPORT: The "Xi'an Model": Reviving Tang Chang'an and China's Imperial Imaginaries

In Xi'an, revival of the former capital of Imperial China carries both local development goals as well as implications for Xi's campaign for "cultural self confidence".

The urban development agenda of contemporary Xi’an has been shaped around a nostalgic vision of China’s past imperial splendor in which Xi’an, and China itself, lay at the center of global trade and influence.

In 2013, fresh from undergraduate degree(s) in history and urban planning from UC Berkeley, I began a 10-month long stint as a visiting Fulbright Scholar at Xi’an’s Architecture and Technology University 西安建筑科技大学. I had studied in Beijing for one semester during my first trip to China in 2009, and the Fulbright program was encouraging more Americans to branch out beyond the Beijing and Shanghai worlds. I’m glad I took them up on this, because I got to experience life in rapidly growing inland Chinese metropolis of Xi’an. Arriving in Xi’an, I found an apartment in a newly constructed complex not far from the Muslim Quarter, just inside the gates of the old city wall, which unlike Beijing, had been virtually entirely preserved since Imperial times. Of course, most foreigners know Xi’an (if they know it at all) for the famous terracotta warriors, relics of the tomb of Emperor Qin Shihuangdi (the first emperor of a unified China) which were discovered by farmers in the 1970s. Xi’an, or Chang’an 长安 “everlasting peace” as it was then called, was the capital of China during its first empire (the Qin and then subsequent Han Dynasties), as well as the Tang dynasty (618–907) considered by Chinese historians to be the peak period of Chinese wealth and influence. Tang Chang’an was one of the world’s largest cities, with a population around 1 million. My time in Xi’an coincided both with a period in which the city was embarking on an ambitious city planning effort to reconstruct the Tang-dynasty era Chang’an through a variety of planning and architectural projects around the metropolis. The “Xi’an Model” may have seemed kitschy and commercialized form of historic preservation at the time (and it still is in many ways), but it prefaced the growing focus on culture and “cultural self confidence” 文化自信 in Xi Jinping’s China—Xi would take power in 2013. While the Mayor who initiated Xi’an’s imperial revival was a target of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign in 2015, the plan’s influence continues to shape the development of Xi’an and the broader turn toward cultural industries throughout China. The Xi’an model shows how nostalgia for China’s bygone era of greatness has been both a tool for boosting the city’s development and economy as well as an deepening a form of what scholar Elizabeth Perry has called “cultural governance” or the turn by China’s Communist Party embrace of its role as a protector of China’s “excellent traditional culture” 优秀传统文化 as a bastion of the Party’s legitimacy.1

Looking back, the “Xi’an Model” seemed at the time a kitschy and commercialized form of historic preservation (and it still is in many ways), but it prefaced the growing focus on culture and “cultural self confidence” in Xi Jinping’s China

The “Revival” of Tang Chang’an

Xi’an had been a popular tourist destination with its complete city wall and Terracotta warriors, but it was’t until 2005 when the city formally embarked on a plan to restore the Tang Dynasty city, the boundaries of which extended over an area far beyond the extent of the Ming/Qing-era walled city, an area that now includes much of the modern city. In 2005, the Mayor of Xi’an Sun Qingyun 孙清云 announced in 2005 the “Imperial City Restoration Plan” 皇城复兴计划 with a total investment of 23 billion yuan ( 3.5 billion USD). Xi’an’s chief planner at the time He Hongxing wrote that, “the meaning of ‘revitalization’ is not to restore the original conditions or repair the old as it was, but how to further highlight the city’s personality through planning and explore a way to create its own unique city characteristics.”2 The goal was to transform Xi’an’s inner city “into a contemporary functioning replica of the Tang Imperial City by 2050” The aims of the 2008-2020 Third City Plan would be continued in the city’s 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015), in which “The government endeavours to reconstruct the old city for the sake of reviving the ‘prosperous age’ of Xi’an as an ancient capital and the hearth of Chinese civilization.”3 Sun would go onto serve as party secretary of Xi’an 2006-2012, and then Deputy Party Secretary of Sha’anxi Province from 2012 until 2015, when he was brought down as part of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.But in many ways, Xi’s continued use of terms like the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people” 中华民族伟大复兴 bears quite a bit of resemblance (and shares the word fuxing 复兴 ) with Xi’an’s plan for its own “rejuvenation” into a simulacrum of Tang Chang’an by 2050—perhaps not coincidentally, the Party’s stated goal for China’s rejuvenation has 2050 as the date for becoming a “Great Modern socialist country.”

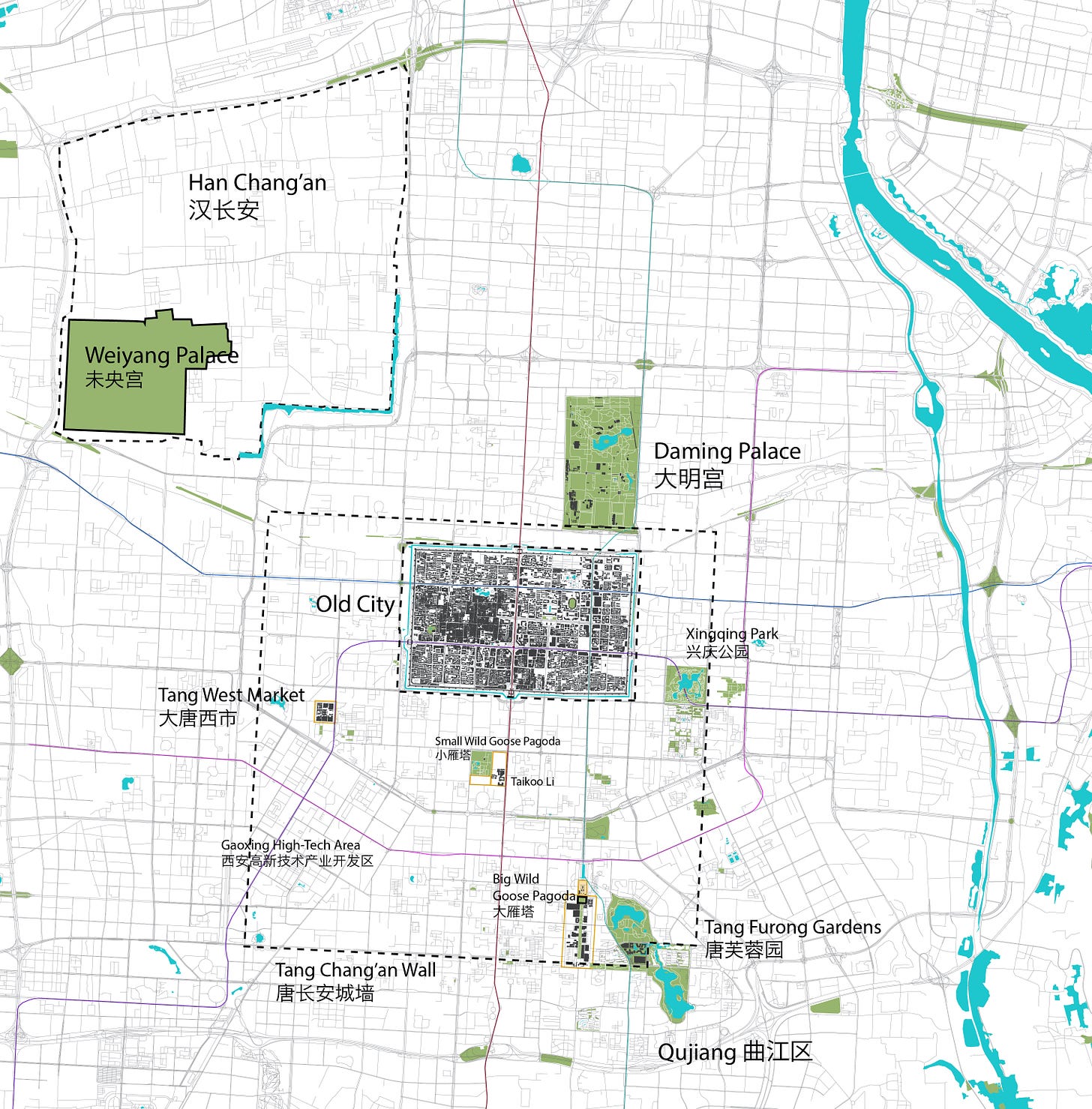

At the time I was in Xi’an, the city had been embarking on a construction craze. much of which centered around restoration and reconstruction of former Imperial pleasure gardens, markets, and palaces. Xi’an, long an inland backwater, was now intent on restoring itself to the status of “international great metropolis” or 国际大都市, a slogan found plastered around various construction sites in the city. The Qujiang Area 曲江区 in the city’s southeast includes the the Wild Goose Pagoda 大雁塔, began to be developed into a new commercial area in 2007, replete with malls, hotels, and food streets and new upscale housing developments. The pagoda dates to the Tang Dynasty and was where the monk Xuanzang copied and translated the Buddhist sutras he brought back from India, a story immortalized in the Chinese classic 西游记 Journey to the West. Nearby is the Datang Furong Yuan 大唐芙蓉园, built on the site of a former pleasure garden of the Tang Dynasty, which at the time lay just outside the southern walls of the capital. The site of the former West Market of Tang Chang’an 大唐西市, once a bustling entrepot of trade with countries from across the Silk Road, was reconstructed to include a museum of relics from the Silk Road and the market, a hotel, and multiple shopping areas. To the north of the main city, the Daming Palace 大明宫 (one of the main palaces of the Tang Dynasty) was being restored to an archaeological park, and even further out in the Northwest there were efforts to recover and reconstruct the Han-era palace complex known as Weiyang Gong 未央宫.

The Central Asian summit of 2023 showcased Xi’an’s Tang revival as a backdrop for China’s regional and global aspirations. But the Tang Paradise park has more regularly become a popular spot for influencers, specifically young people dressing up in Han-style clothing or hanfu. Xi’an’s rebuilt heritage locations are not merely high-level stagesets, but are actively embraced by city residents and tourists. Of course, historic preservations and scholars may take issue with the idea of rebuilding fake replicas of long destroyed historic sites. But as many heritage scholars have pointed out, notions of “good” historic preservation are culturally specific. Generally in Asia, including Japan, wood structures were seen as organic and constant maintenance and reconstruction was assumed. This is a very different approach than in the West, where preserving objects and buildings as clost to their “original” form as possible is often considered the gold standard of historic preservation.

The urban development agenda of contemporary Xi’an has thus been shaped around a distinctly nostalgic vision of China’s past imperial splendor in which Xi’an, and China itself, lay at the center of global trade and influence. Despite its status as a second-tier city in today’s China, Xi’an’s development has and is now increasingly intertwined with Xi Jinping’s push for “cultural self confidence” and “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” This role for the Western metropolis was on full display in May 2023, when Xi and his wife Peng Liyuan hosted the leaders of central Asian nations with a ceremony replete with decadent Imperial clothing and performances. The ceremony’s closing banquet occurred in front of the Tang Lotus Garden. Xi’an’s nostalgic cityscape had become a showcase for China’s revived international ambitions.

Historical Reconstruction as City Development Strategy

In 2007, the Qujiang District Government rezoned industrial land on the edge of Xi’an and designated the area as a cultural cluster. In 2007, the district was awarded the title National Cultural Industry Model Park. The Qujiang Area is home to the most commercially oriented new theme parks in Xi’an: Tang Paradise (唐芙蓉园), and Big Wild Goose Pagoda 24 Hour City, a bright commercial district stretching south from the pagoda.

Daming Palace 大明宫

One of the first large projects to commence was a restoration of the Tang-era Daming Palace 大明宫, which lies just to the North of Xi’an’s main train station. This project required the relocation of 100,000 residents, what anthropologist Michael Herzfeld refers to as “spatial cleansing.”4 The park opened in October 2010. The front gate has been reconstructed. Inside, much of the park is open, but several of the main halls have been reconstructed or partially reconstructed with a sort of skeletal frame to suggest the outlines of past buildings without fully reconstructing them.

Tang West Market 大唐西市

Located near the western wall of Chang’an, the Western Market was the logical choice for foreign traders arriving from the West . “Chang’an had two great markets, the Eastern and the Western, each with scores of bazaars. The Eastern Market was the less crowded of the two. The Western was noisier, more vulgar and violent, and more exotic.”5

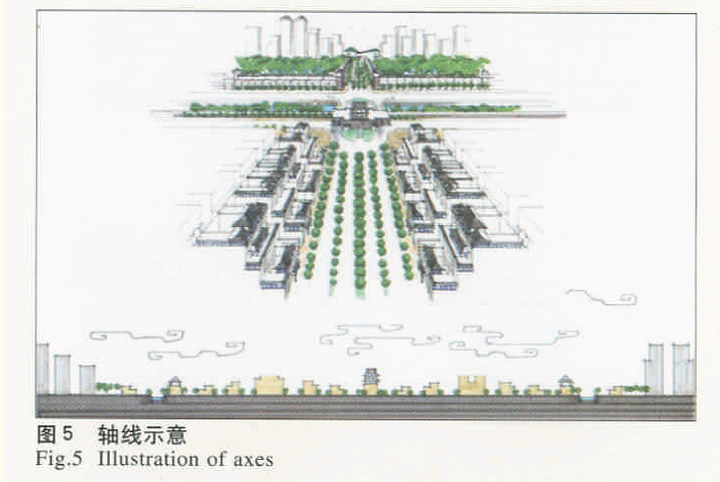

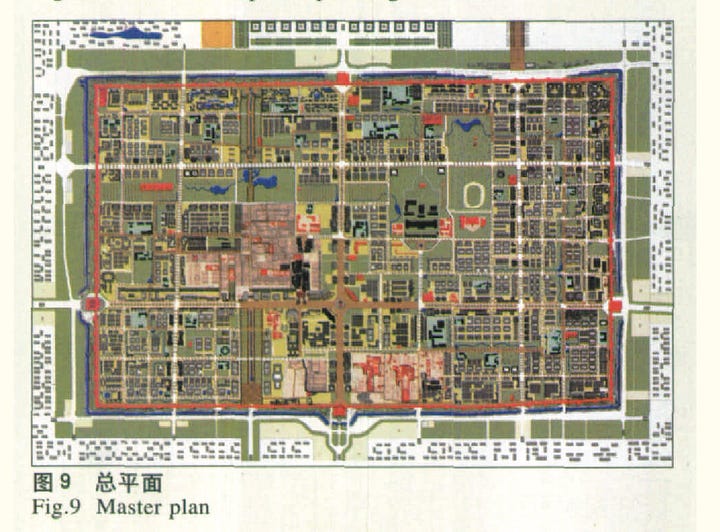

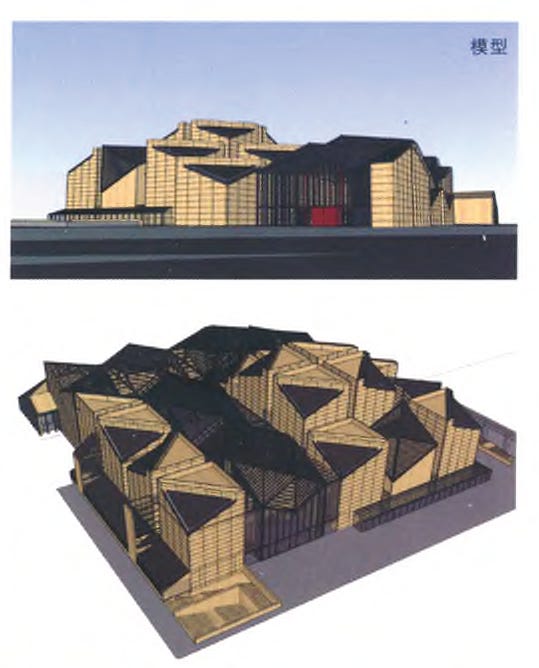

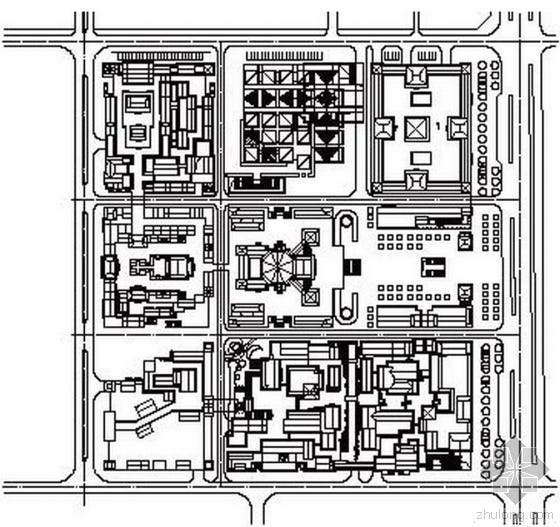

The original West Market was subdivided into a 3 x 3 grid of blocks or fang, forming 9 squares, resembling the ancient Chinese 井田or “well-field” layout of classical city planning.6 This general layout was retained in the new project, with each block being devoted to a different use. Most of the 365,900 square-foot complex was designed in the “New Tang Style”, featuring low-slung rooflines and longer roof wood beams than what is typically found in later Ming and Qing Dynasty architecture. However, the museum, which was sited at the central north block, was designed by Liu Kecheng, a prominent Xi’an-based architect. This building is deconstructed take on the “Tang style”

The city government set up a special company to develop and run the site, the Xi’an Datang Xishi Zhiye Youxian Gongsi (西安大唐西市置业有限公司), which has maintained general control and management rights of the market and the 8 billion RMB ($1.26 billion) cost of the project. This entity received investment and support from Hong Kong Cosco Group and Beijing Wanchang Investment Group7. Today, the company is known as the Tang West Market Group (Datang Xishi Jituan), and manages assets worth $8 billion including property and hotels, the cultural companies that run arts and crafts markets, and media units that produce content and run events related to the market and the Silk Road across China.

The Qujiang Model: Real Estate, Tourism and Cultural industries

The Qujiang District in the Southeast of Xi’an has seen the largest scale new construction and redevelopment as part of the Tang Imperial City Revitalization Plan. The centerpiece of this is the shopping promenade running south from the Big Wild Goose Pagoda, and the Tang Paradise (Furong Yuan) park. But the development of Qujiang was not merely about rebuilding physical spaces, it was also a broad strategy encompassing the creation of specialized cultural industry promotion companies as part of the development process. The Qujiang Cultural Industry Group 曲江文化产业集团 was actually founded in 1995 from investment of Xi’an Municipality and Qujiang District, 10 years prior to the Xi’an Tang City Revitalization. Other cultural companies include Xi'an Cultural and Business District Group, Duling Urban Ecological Leisure Zone, Yanxiang Road Cultural and Creative Group, Daming Palace Cultural, Commercial and Tourism Group, among 900 other entities. According to an article in 2010, The Qujiang Scenic Area had received 30 million tourists, with “tourism income of 1.5 billion yuan and a cultural industry added value of 7.6 billion yuan, accounting for more than 40% of the total cultural industry in Xi'an.” The “Qujiang Model” is thus a uniquely Chinese form of urban cultural industry development, a variation of local government entrepreneurialism in which real estate, tourism, and cultural heritage services are combined as a generator of economic growth.

Tang Paradise 唐芙蓉园

This theme park features Tang-style architecture surrounding a lake with gardens, performances of Tang-style music and theater, and various evening light shows.

Big Wild Goose Pagoda “24 hour city” 大雁塔不夜城

The Big Wild Goose Pagoda “不夜城 24 hour city is a long North-South promenade lined with commercial and recreational buildings running from the pagoda in the north to the Tang Paradise in the South. It began construction in 2002, thus predating the 2005 plan.

Xi’an Taikoo Li (Small Wild Goose Pagoda) 西安太古里 -小雁塔 (UNDER CONSTRUCTION)

Hong-Kong based Swire has developed several popular commercial shopping districts such as Beijing’s Sanlitun Taikoo Li (formerly the Village), Chengdu’s Taikoo Li8. Now, Xi’an will have its own Taikoo Li, a 200,000 sq m commercial district being developed next to the Small Wild Goose Pagoda on the plot of Xi’an Bowuyuan, which also includes the Xi’an Museum. Like its Chengdu counterpart, Xi’an’s Taikoo Li will emphasize traditional culture and traditional Chinese style: its site planning will permit visitors to see archeological excavations of the ward (urban district) of Tang Chang’an. Xi’an’s Taikoo Li continues the city’s focus on using historic restoration as a tool of property development, and follows from Swire’s successful formula in Chengdu.

Perry, Elizabeth J. “Cultural Governance in Contemporary China: ‘Re-Orienting’ Party Propaganda.” In To Govern China, edited by Vivienne Shue and Patricia M. Thornton, 1st ed., 29–55. Cambridge University Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108131858.002.

和红星. “城市复兴在古城西安的崛起——谈西安‘唐皇城’复兴规划.” Cheng shi gui hua, no. 2, 2008, pp. 93–96, https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1002-1329.2008.02.019.

Zhu, Yujie. “Uses of the Past: Negotiating Heritage in Xi’an.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 24 (June 29, 2017): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1347886.

Herzfeld, Michael. “Spatial Cleansing: Monumental Vacuity and the Idea of the West.” Journal of Material Culture 11, no. 1–2 (July 1, 2006): 127–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506063016.

[1] Schaefer, Edward. “The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of Tang Exotics.” U.C. Press, Berkeley, 1977.

“An Analysis of the Form and Historic Value of Tang West Market,” Bi Jinglong and Wang Hui. In Huazhong Jianzhu, February 2011. Pg. 146.

Xu Min, “The Tang West Market is Coming”, in Xin Xibu 2005 大唐西市呼之欲出, in 新西部

Datang Xishi Jituan Website. http://www.dtxs.cn/

[1] Michael Keane, China’s New Creative Clusters: Governance Human Capital, and Investment. (London: Routledge, 2013)

https://www.swireproperties.com/en/portfolio/current-developments/taikoo-li-chengdu/