How is China's "Eastern Data Western Compute"(东数西算) developing?

A progress report on China's plan to boost "computing power" through nationwide cloud computing infrastructure

In 2018, Apple moved most of its data for China-based users to cloud computing servers in southwestern Guizhou’s Gui’an New Area. This decision reflected a reality since China’s 2016 Cybersecurity Law, that in order for foreign technology firms to operate in China they would have to store user data within the country. Apple no doubt saw this as a necessary compromise to ensure its continued operations in China and maintain its presence in the country that still accounts for 20% of its sales. But why Guizhou?

To answer this question you have to look at how this southwestern metropolis has in recent years cemented its status as a hub for data and cloud computing in China. Lying far from China’s eastern metropolises, Guizhou appears an unlikely location for cloud servers. Typically, data centers are located in or near major urban centers in close proximity to customers—locating as close as possible to end users is critical for the fast speeds and low latency crucial to most types of data operations. But data centers also require large amounts of land and energy. China’s Western regions are less densely populated but are abundant in energy resources including coal, natural gas, as well as solar and wind potential. Land and energy costs are lower than in Eastern cities. Guizhou’s success also benefited from a confluence of leadership moves, including the so-called “Guizhou connect” faction of close Xi associates Chen Min’er, who was party secretary, and Chen Gang, who helped drive development and gain central endorsement of Guizhou’s plans.1

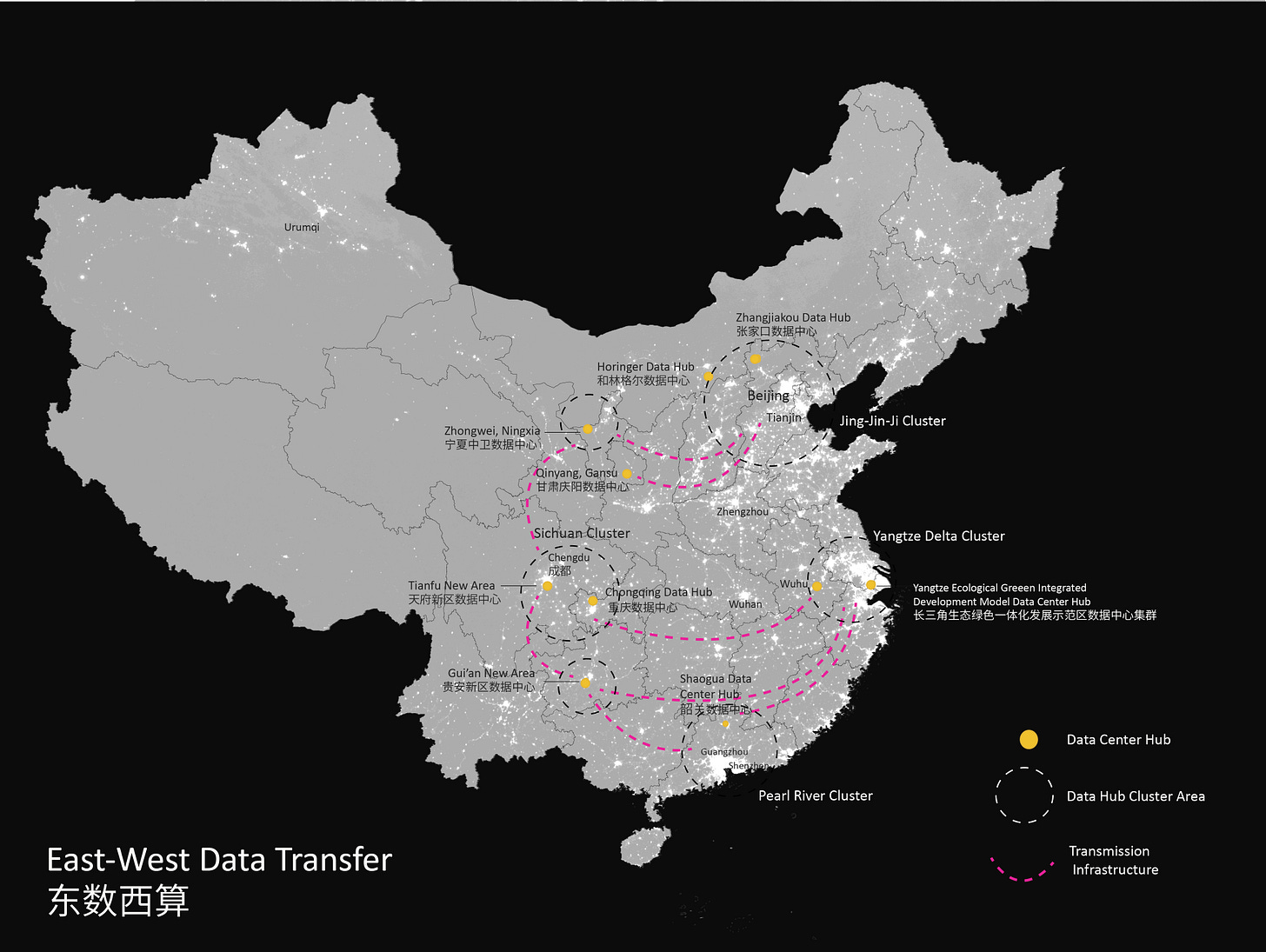

In 2021, China’s National Reform and Development Committee (NRDC), the nation’s economic planning body, announced an ambitious project called 东数西算(Eastern Data Western Compute— I will refer to it “EDWC”) to scale up Guizhou’s experiment into a nationwide infrastructure system, creating 10 “ national data center clusters” (国家数据中心集群) and 8 “computing hub nodes” 算力枢纽节点.2 The project has had significant input from technical institutes , namely China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) 信通院, a key research body under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) 工业和信息化部. The plan followed from several earlier policies or concepts, beginning with the 2018 term “new basic infrastructure” 新基建 issued by the central economic working group, and the 2020 plan released by NRDC for “speeding up the Coordinated Big Data Center System Innovation”3 The plan also fits with longstanding regional development efforts such as the “China Western Development” 西部大开发 policy, adopted in 2000.

The plan outlines 10 cloud computing hubs across 8 regions, including Guizhou, but also in: Qinyang, Gansu province; Zhongwei, Ningxia; and Horinger near Hohhot, the regional capital of Inner Mongolia. Several additional hubs are envisioned closer to major metropolitan areas of Chengdu-Chongqing (Tianfu New Area, and Liangjiang New Area), Zhangjiakou (NW of Beijing), Wuhu (outside Nanjing), a new industrial park West of Shanghai, and Shaoguan (north of Guangzhou). While some of the clusters, like Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, and Chengdu-Chongqing already were home to significant cloud server clusters, some of the planned clusters have only been developed following the announcement of the national plan—namely Zhongwei and Qinyang.

Planned Investment and Results to Date

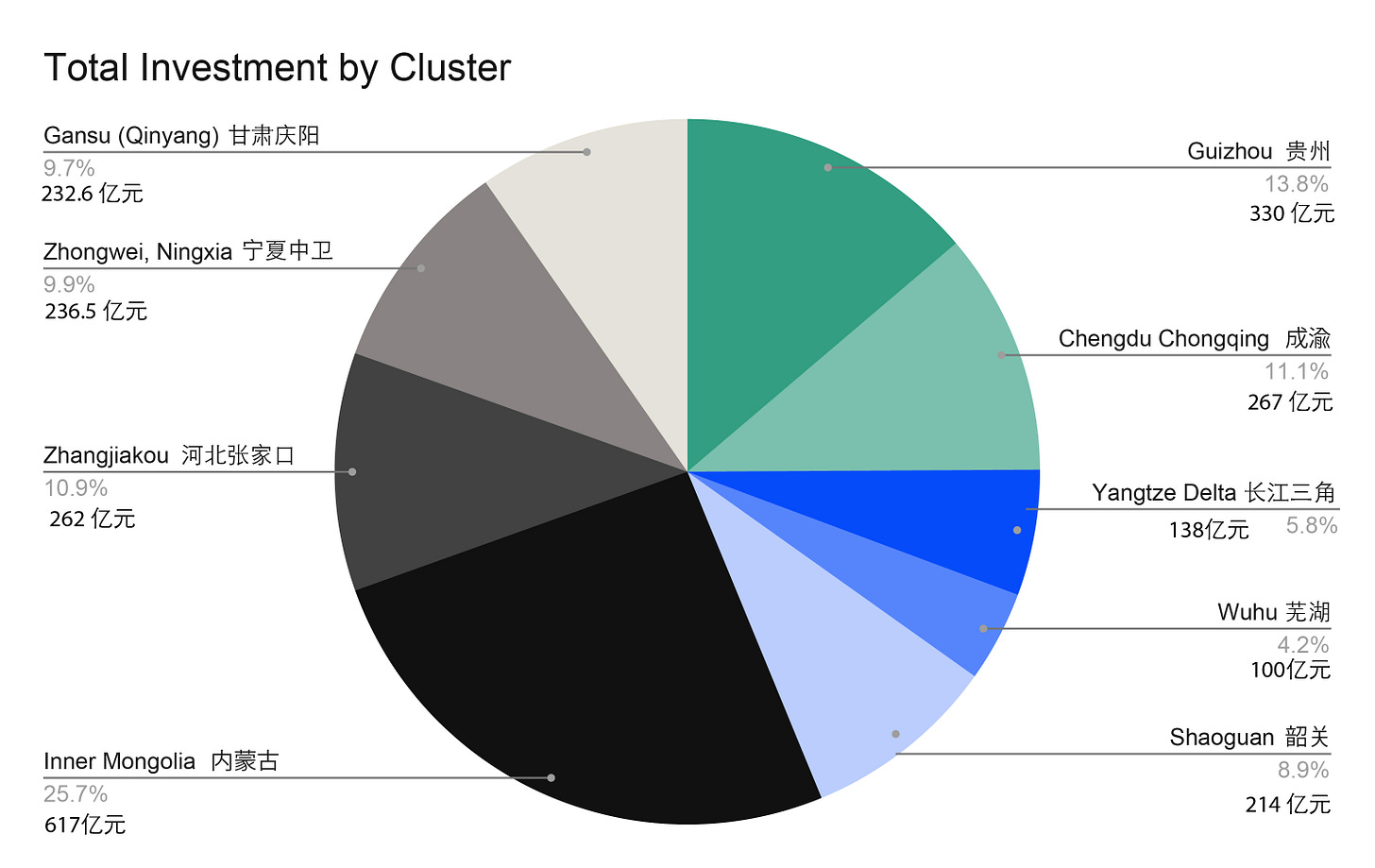

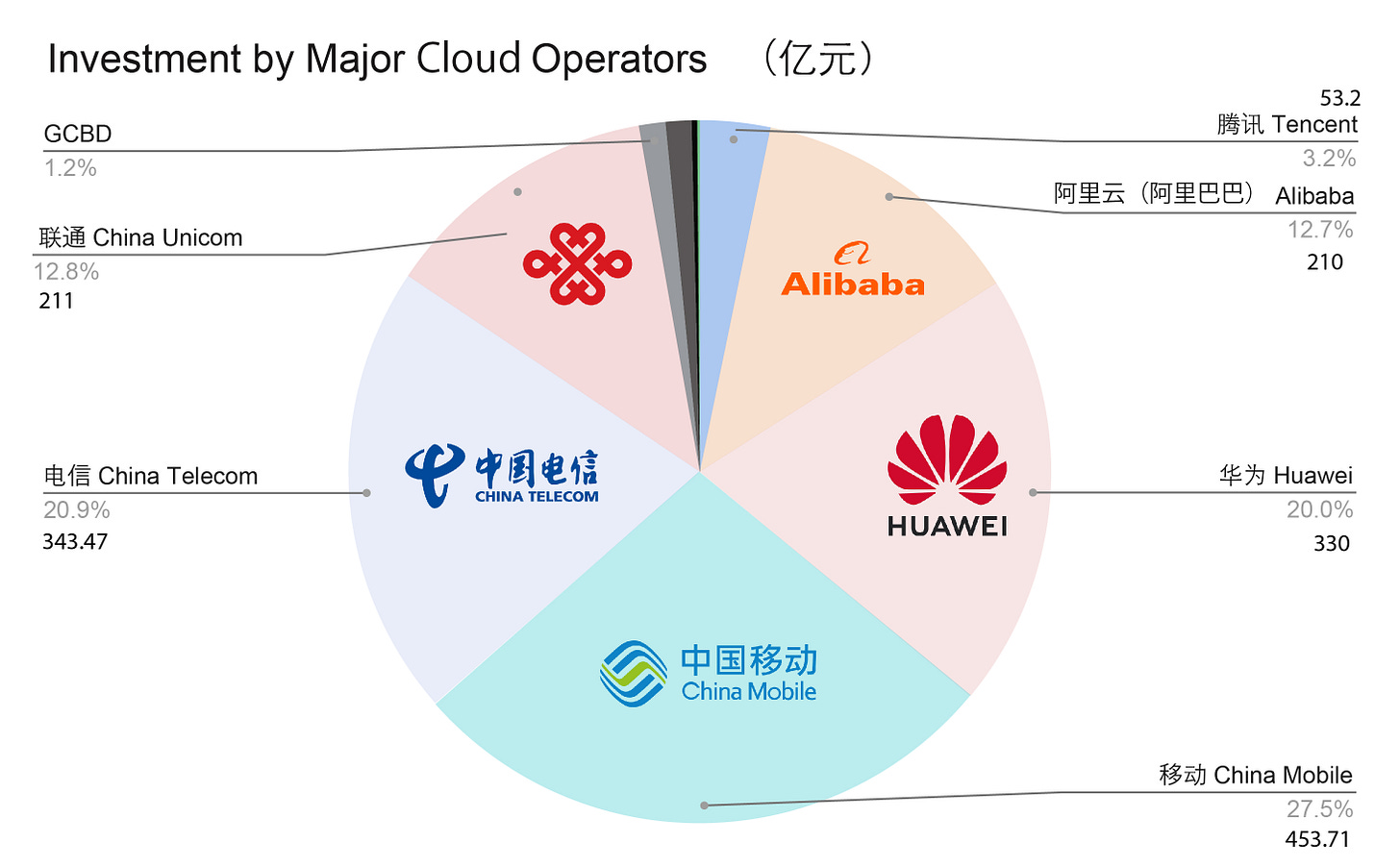

The overall planned investment of the EDWC varies, but statistics from the NRDC report an estimated total cost of 4000-5000 亿元 (4-500 Bn RMB or about $56-70 bn) For comparison, the N-S Water Transfer is estimated to have taken 240 bn RMB in investment by 2014. Based on gathering publicly available reports of data-center investment in the hub locations to date ( as of May 2024), the following tables and charts show the breakdown of investment by location and by company. There was some media attention on the plan when it was announced, but there has been very little follow up on the actual clusters outlined, and the scope and implications of projects built so far. Through scraping of reports on data center openings from news and government websites, I compiled a progress report detailing the completed or planned investment by cluster (below), and by cloud operator. Figures are in 亿元 (100 mn RMB). I could account for investment of 2399 亿元(239 billion Yuan or $33 bn USD), suggesting more than half of the project’s planned investment scope has already been reached. A great deal of the investment for the project is coming from various companies shown in the second chart. However, it is hard to know precisely how much in subsidies or incentives (such as tax breaks or discounted land provision) has been given by local governments to cloud computing companies.

In 2019, Apple completed its 2nd data center in China in Ulaanqaab, Inner Mongolia—a short distance from regional capital Hohhot. While private cloud providers (Huawei, Tencent, Alibaba) lead China’s cloud computing market, the EDWC calls for China’s big 3 telecoms, currently with around 20% of the country’s IDC market, to play a “leading role as the main implementing force for the East-West Data Transfer.”4 EDWC could shift greater influence in China’s cloud computing infrastructure from private platform firms (Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei currently account for around 75% of China’s cloud computing market) to state-owned telecom operators. Globally, U.S. firms still dominate, with only Alibaba’s Ali Cloud (阿里云) cracking into 4th place with 4% of global market share. By tracking completed or planned investment in each cluster of the E-W Data Plan, we can see that the top operators for cloud centers are China Mobile and China Telecom, followed by Huawei (see below). This suggests China’s state-owned and “national champion” Huawei are playing a leading role in the project, and could see their share of China’s internet data center infrastructure grow relative to commercial market leaders Tencent and Alibaba, which are comparatively minor investors in E-W Data Hub projects—though Alibaba invested early on in areas that are now part of the plan, such as Zhangjiakou. And while China’s 3 telecoms can be considered “primary network operators” (运营商) China’s commercially oriented cloud providers (Tencent, Alibaba, Huawei) will likely continue to dominate the commercial cloud computing market.

Logic: Boosting National Computing Power, remedying spatial imbalances

The plan’s key tasks:

Strengthening Green and Intensive Construction

Promoting Core Technology breakthroughs

Accelerating network interconnections

strengthening energy supply guarantees

Enhancing energy consumption monitoring and management

Improving computing power service levels

Promote orderly data circulation

Deepening intelligent data applications

Ensuring network and data security

“As the foundation for the operation of the digital economy, big data centers can not only effectively drive investment in upstream and downstream industries such as information technology R&D and manufacturing, communication networks, and energy, but also promote the comprehensive digital transformation and upgrading of the economy and society, further smoothen the circulation and application of data elements, and contribute to continuous strengthening. Improving and expanding our country’s digital economy plays an important and fundamental role.”

Note the use of the term “data factors” or “elements”—the notion of factors of production is a Marxist concept. In CCP lexicon, data has now been enshrined as a factor of production5, on par with land, labor, and capital (Marx’s original formulation). The E-W Plan can therefore be seen as part of a series of recent initiatives to improve China’s regulation and infrastructure for data, such as the broader “Digital China” initiative 数字中国6。

Of course, “cloud computing” is a broad category that generally can be divided into 3 specific types of cloud computing, including Infrastructure as a Service (Iaas), Platform as a Service (Paas), and Software as a Service (Saas). Private cloud centers can be built for customized use of specific companies (referred to as enterprise data centers 企业数据中心), but public clouds(互联网数据中心)typically provide services for a range of third-party clients. Finally, there are national data centers (国家级数据中心) such as quantum or advanced computing data centers. While many data centers have been built through private investment, the East West Transfer project is framed as boosting China’s “national computing power” or 算力.7 Data clusters in the plan are seeing investment in a variety of these types, some enterprise-driven, others publicly oriented, and others built as national data centers.

Challenges

In China’s current market, leading providers have tended to locate cloud and data centers near customers in major metropolitan regions. The E-W Data Transfer Plan aims to disperse some of this to inland regions. Part of the technical problem that arises is how to optimize the transfer of data between computing hubs and end users, and reduce latency. For example, Huawei has outlined several network technology innovations that it claims will facilitate this.8 In the interim, data centers in inland locations may ultimately be better suited for certain types of data functions that do not require extra low latency, such as storage, e-governance or public services. As the plan notes, “

For nodes such as Guizhou, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and Ningxia, rich in renewable energy, with suitable climates and significant potential for green development of data centers, we will focus on improving the quality and utilization efficiency of computing power services. By fully leveraging resource advantages and solidifying network and other basic guarantees, we will actively undertake nationwide non-real-time computing power needs such as background processing, offline analysis, and storage backup, creating a national base for non-real-time computing power.9

This suggests that the remote Western data centers, which will have greater latency for customers in main urban areas (located further away), will prioritize “non-real time computer needs like background processing, offline analysis. and storage backup,” while the most intensive and time-sensitive forms of data services (i.e. real-time financial transaction or trading), will be prioritized in the data centers in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Yangtze River Delta, Chongqing-Chengdu, and Pearl River Delta regions, where end-end one way network latency will be kept within 10 milliseconds—while in remote regions, latency may be kept within 20 milliseconds.

Comparison With Other National Infrastructure Projects

The E-W Data Transfer is explicitly compared to earlier large-scale nationwide projects that sought to balance distribution of resources (or production factors) across China. This includes the North South Water Transfer 南水北调, the E-W Power Transfer 西电东送, and West–East Gas Pipeline 西气东输 (begun 2002). The 东数西算 is discussed as the “north-south water transfer for the digital age.” As the aqueduct transfers water from wet South to the arid North, the E-W Data transfer remedies a different kind of spatial imbalance—the current concentration of population and data centers in large eastern metropolises (See below figure10, with the relative abundance of energy resources and lower cost of energy in western China. The project can also be seen as part of the China Western Development (西部大开发) plan, which was announced by Jiang Zemin way back in 1999, but a general concept for developing China’s West that has been in subsequent initiatives.

Local Development: E-W Data Sites 东数西算游记

While the project is “nationwide infrastructure”, there are significant spatial and economic implications for the various locales where data center clusters are being developed. In each site, local governments are engaged in construction of new data center industrial parks, subsidies to data center operators, and other incentives to spur the creation of data infrastructures in their jurisdictions. The E-W Data Project is thus different from the aforementioned national infrastructure projects in that it is primarily an urban location-specific development project. Although adding additional transmission capacity to improve network connectivity between data centers and population centers is also part of the plan.

Guizhou (Gui’an New Area) 贵州贵安新区

Guizhou can be considered as the first cluster to be developed and the inspiration for the East West Data Transfer Project. Most of the new cloud servers are in the Gui’an New Area, a “national level new area” developed just outside the capital Guiyang.

Inner Mongolia 内蒙古

Inner Mongolia is becoming the key data region in Northern China, with two main clusters in Horinger 和林格尔 and Ulaanqaab 乌兰察布. Apple built its second data center in Ulaanqaab, and Huawei has its second largest cloud facility (after Gui’an) here.

Qinyang, Gansu 甘肃庆阳

About 190 km NW of Xi’an, Qinyang is a remote prefecture-level city in Gansu on the Loess plateau.

Zhongwei, Ningxia 宁夏中卫

Shaoguan 韶关 (north of Guangzhou)

Shaoguan currently has projects such as the provincial big data industrial park "South China Data Valley" and Huashao Data Valley, China Unicom Smart Customer Service Southern Center, and China Internet Finance Association Southern Data Center.

Yangtze River Delta Integrated Development Zone 长三角综合发展模范大数据中心

Just west of Shanghai is a new development zone where a few large data centers are already under construction or planned, including from China Telecom, Alibaba, Ucloud, China Mobile.

Wuhu 芜湖 (outside Nanjing)

Zhangjiakou, Hebei 河北张家口 (north of Beijing)

Located just 150 km NW of Beijing and the site of the Beijing winter olympics, Zhangjiakou saw a large data center built by Ali Cloud in 2016. With abundant wind and solar exposure, Zhangjiakou has good potential for renewable energy. Most of the data center construction is occuring in Zhangbei County, to the north of the main city area.

Chengdu, Sichuan (Tianfu) 城府天府新区数据中心

The Tianfu New Area was approved as a “national-level new area” by the State Council in 2014 on the southern outskirts of Chengdu, which has grown into a hub for digital and technology innovation in SW China. Many of the new cloud computing centers are being located here. The Chengdu Supercomputing Center (pictured below) is one of the most striking architectural projects of any data center, designed to serve as a symbol of futuristic computing technologies.

Chongqing Data Hub 重庆大数据中心

Implications

While the ultimate implications of the East-West Data Transfer Project remain to be seen, already the project has mobilized investment in data center construction and increased data center capacity. The outcome of the project may depend on how much subsidies and government support are required to attract private investment in data centers that might not otherwise be considered profitable or feasible by companies. However, because much of the investment in the project is coming from state-owned enterprises (the big three telecoms), these companies can obtain greater government support. Will new data parks boost development of inland regions? Again, this too remains to be seen. So far, Guizhou and Inner Mongolia have been the most successful Western areas to attract new data centers. The new clusters in Gansu and Ningxia are still in their infancy. Also, its not clear that data centers alone can be anchors for broader-based innovation in digital services. Data centers provide minimal employment, although they do boost connectivity and supply of data services for the regions where they are built, thus potentially driving further investment in digital sectors. Energy efficiency is another areas where the plan could have a positive impact, as the plan emphasizes improving the PUE “power usage effectiveness” ratio-in other words reducing the amount of energy needed for cooling and air-conditioning. 11

How the project unfolds will have implications for China’s overall “computing power” as well as the geographic distribution of its digital sectors. Although, it’s unlikely that the project will significantly reduce the concentration of talent and investment away from core urban areas. Chengdu and Chongqing already comprise a vibrant economic cluster in Western China. New data hubs planned in Gansu and Ningxia may also boost connectivity in the nearby cities of Lanzhou and Xi’an—which is the largest metropolis in Northwest China.

From a political economy perspective, the E-W Data Transfer has the potential to shift power in the IDC market from private technology platforms (Tencent and Alibaba) towards State-owned enterprises. As a report by China Unicom notes, “as the national team (国家队)of communication network infrastructure, the 3 major operators actively promote the national internet backbone and connection point construction”12. This fits with the broader trends in the “new era” following the so-called “war on technology platforms”13 that China’s technology regulators oversaw in 2021 against Alibaba, Didi and other platform firms. China’s policymakers have decided the country needs additional data infrastructure, and they would like to give state-owned enterprises a key role in building that infrastructure. That doesn’t mean private operators will be excluded, but for critical national infrastructure, the Party-State cannot risk leaving it purely to private firms.

Liu, Kevin Ziyu. “Making the China Data Valley – The National Integrated Big Data Centre System and Local Governance.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 0, no. 0 (2024): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2024.2311808.; https://thediplomat.com/2021/08/chen-gang-a-dark-horse-to-lead-chinas-strategic-technoindustrial-policy/

National Reform and Development Commission 国家发改委 《全国一体化大数据中心协同创新体系算力枢纽实施方案》May 2021

National Reform and Development Commission 国家发改委 《关于加快构建全国一体化大数据中心协同创新体系的指导意见》, 2020

China Unicom "East West Data Transfer: Professional Research Report” (东数西算 2022 专题研究报告) China Unicom Research Institute, 2022

CAICT 中国信通院 “Data Factors White Paper” 数据要素白皮书 (2022)

CCP Central Committee, State Council 中共中央 国务院印发《数字中国建设整体布局规划》”Overall Plan for the Construction of a Digital China” https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2023-02/27/content_5743484.htm

Qianzhan Industry Research Institute。“Big Country Computing Power” 大国算力:2022年东数西算机遇展望 (2022)

https://www.huawei.com/en/huaweitech/publication/202202/eastern-data-western-computing-network

National Reform and Development Commission 国家发改委 《全国一体化大数据中心协同创新体系算力枢纽实施方案》May 2021

CAICT 中国信通院。"“China Computing Development Guide White Paper” 中国算力发展指数白皮书 (2023)

PUE: “The ratio of the total amount of energy used by a computer data center facility to the energy delivered to computing equipment.” (Wikipedia). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_usage_effectiveness

China Unicom (2022)

Collier, Andrew. China’s Technology War. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

OTHER

China Mobile “Computing Force Network Technology WhitePaper” 算力网格技术白皮书 (2022)

This is a really great topic.

Thank you. This is very interesting!