Over the first few months of the Trump administration, I’ve found my head spinning—mostly because of the sheer volume of extreme policies and actions taken here in the U.S. But recently I’ve also had my head spinning from the bipolarity of coverage on China. Some of this has to do with changing prognostications about how Trump’s actions will or will not affect China. Pundits and experts of all stripes are trying to come to grips with a fickle and constantly changing tariff policy here in the U.S. But there’s also been a huge whiplash in terms of how commentators here in the U.S. (and elsewhere) are viewing China’s outlook in light of these evolving dynamics.

Nonetheless, It’s difficult but essential to keep two paradoxical truths about China in the current moment in our heads at one time:

China has seen its domestic economy slump over the past five years or so, largely following the severe Covid-19 lockdowns and real estate downturn, and the economy has yet to recover from this.

There are several areas of China’s economy in which China has continued to go from strength to strength, particularly manufacturing of electric vehicles, clean energy, and other technologies

Because of China’s sheer size its possible and indeed likely that these two paradoxical situations will continue to coexist for some time, no matter how the Trump tariff war will play out. In this post, I’ll briefly touch on a few dynamics and offer my thoughts on why these matter for policymakers, investors, and anyone interested in “getting China right” (or at least, not getting it entirely wrong) in the near future.

Review of Past 5 Years; “How did we get here?”

The worst of times

The best of times

How did we Get here? Covid 19 and the whiplash of sentiment on China

First of all, its important to review briefly the past five years or so of conventional wisdom on China to see just how often the narrative has flipped. Let’s recall back to the years leading up to Covid. Trump’s first more limited trade war largely failed to put any dent in China’s progress, and Trump was hailed by China’s internet sphere as Chuan Jianguo 川建国 “the founder of the [Chinese] nation.” So during this period before Covid, China’s growth and dynamism was perhaps at its high point. It was also during this period when Xi Jinping began to talk about “changes unseen in generations” 百年大变局 in his view that the East was rising and the West was declining.In 2017, Xi used the term “profound changes unseen in a century”, or bainian wei you zhi dabianju to describe what he viewed dramatic changes in the world order, encompassing technological transformations but also a shift away from a U.S. or Western-led global order.1 As Jin Canrong, Dean of the School of International Relations at Renmin University, put it in 2019, “after the fourth industrial revolution, the productivity of the East is likely to be ahead of the West, or at least a balance between East and the West will be achieved. This is the most important change among the three changes unseen in a century.”2

The pandemic was a watershed moment. At first, the outbreak of the epidemic in Wuhan shattered Chinese faith in the Communist Party’s governance, epitomized by the rare outbreak of anger at the government’s coverup and delay in responding to it. But by the summer of 2020, with the virus successfully contained in China and spreading like wildfire across the rest of the world, China's leadership began to look comparatively good. At the end of 2020, China had come up with a system of containing the virus through strict controls on mobility, the introduction of “health codes” for intercity travel. It was supplying essential goods to the rest of the world. But anger at the rest of the world towards China, fomented in some cases by politicians like Trump, lead to a continued freeze in relations. After Biden’s victory, the two sides began exploring restoring a “floor” of normalcy in what was spiraling into all out cold war. At a March meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, the Chinese delegation lead by Wang Yi and Yang Jiechi excoriated the Americans, telling them that they had no right to criticize China and saying that China had made great strides by controlling the virus.3 This moment was a point at which China’s leaders were feeling emboldened by the control of the virus and the comparative failings evident in the U.S. and other Western nations’ responses.

The Worst of Times?

However as 2021 progressed, the situation in China became less sanguine. The effect of continued lockdowns and travel code restrictions brought down the popular mood and the economy. Xi Jinping was overseeing a crackdown on his own “platform firms” of Alibaba and Didi, which sent shares of Chinese tech giants cratering and brought down investor and consumer confidence. In 2021, a default by home developer Evergrande triggered the property downturn that has continued to this day. Real estate growth, a major economic engine and source of local government revenues, has since dried up.

When I visited China for the first time since Covid in 2023, and again for a longer period in the summer of 2024, I was struck by the pervasiveness of pessimism expressed by almost everyone I talked to (I wrote about my trip last summer, here). In city after city I heard how local governments were out of money, a point backed up by data.4 Housing projects lay unfinished. The value of homes had decreased. A friend in Beijing told me how his family was trying to sell a property in an advantageous location near high-tech parks in Zhongguancun but couldn’t, and even if they could the price they would fetch would be far lower than what the property had been worth a few years back. Artists talked about tightening space for free expression. The dominant word I heard though was not really about the U.S. but about China’s own internal “involution” or neijuan, described to me as a phenomenon of overwork and competition leading to diminished returns for everyone. Sure, people admitted, there were pockets of exceptional dynamism. But these didn’t seem to matter much for most people’s overall financial situation or sentiment about the future.

The Best of Times? Manufacturing and innovation juggernaut

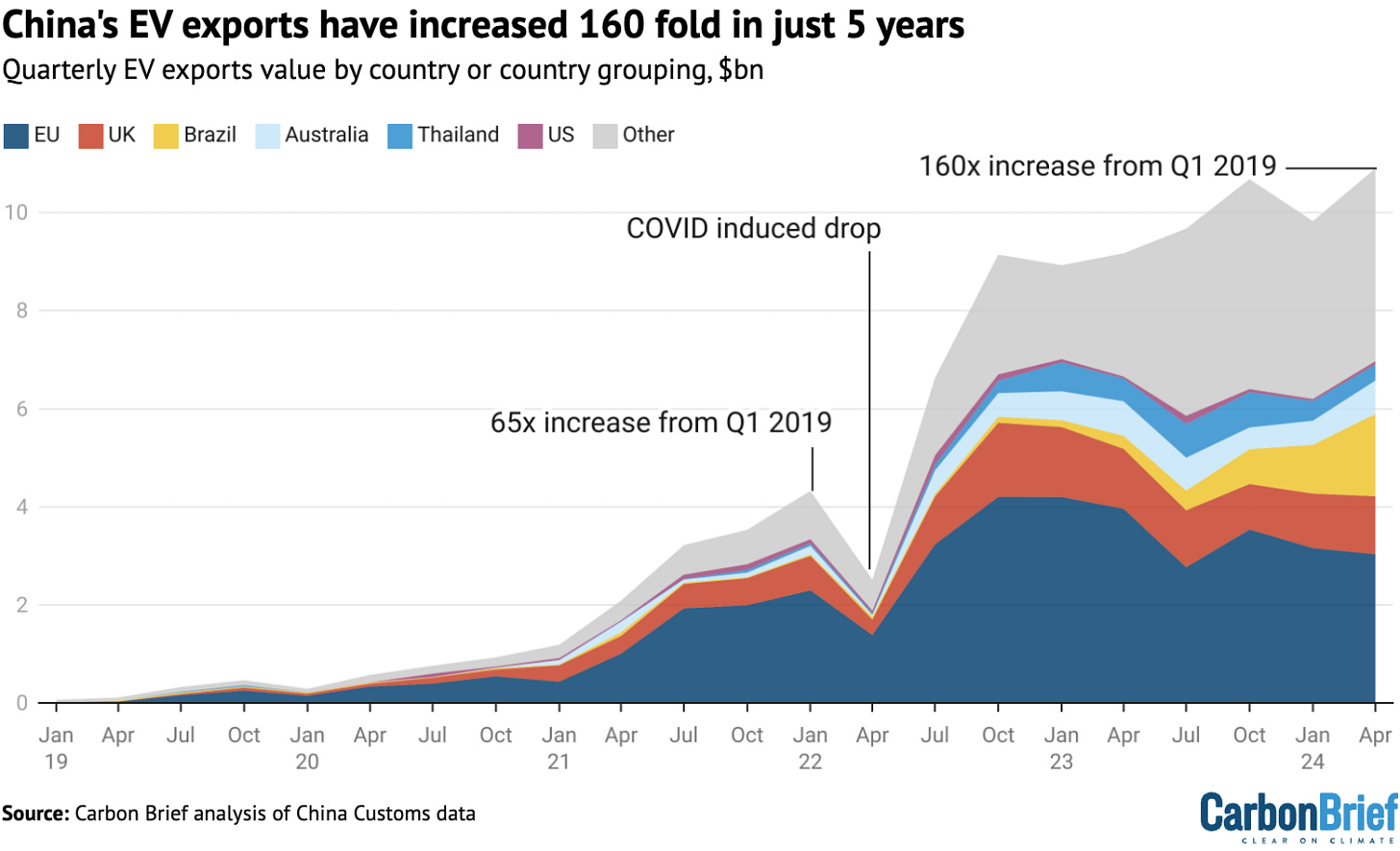

Despite the overall downturn in the property markets and economies, the last five years have been remarkable for the juggernaut of Chinese manufacturing and innovation. The main evidence of this is China’s success in becoming an electric vehicle powerhouse.5 China has rapidly overtaken previous car exporting powerhouses Japan and Germany. While there are basically no Chinese EVs available in the U.S. due to current tariffs on EVs, the EU has become a significant market for Chinese automakers, as are developing countries in South America and Southeast Asia. Criticism has been levied at China’s “overcapacity” in manufacturing, but Trump’s tariffs could ultimately lead to greater Chinese footprint across the world’s major auto markets outside of the U.S. But there is also the situation of “excess competition” as there are around 200 manufactures of EVs in China—many may consolidate or disappear in the coming years.6 And fear of harm to country’s domestic automakers, such as in Europe, may lead to greater restrictions on Chinese EV sales in core international markets.

Implications

It’s worth reflecting on what the bipolarity in China watching sentiment in the West actually means. One the one hand, the extreme views of China say more about the anxiety in the U.S. and West than China itself. China’s rise has challenged the U.S.-led order, and the U.S. itself has seemed to lose faith in the system of free trade it built. China is often portrayed by the media, and by Trump and allies as a threat that the U.S. must defeat in a “Second Cold War.” On the other hand, there is a persistence of the “China is about to collapse” idea pushed for years by those like Gordon Chang and Frank Dikötter who has called China an “empire of illusion.”

However, the bipolarity on China is not only in the eye of the beholder. The current reality in China is in fact paradoxical. The success of manufacturing and innovation in certain high-tech sectors coexists with widespread economic stagnation in the rest of the economy as the hangover from the property boom and bust has not yet abated. The growth of high manufacturing sectors in China has not yet (and may not for some time) lead to growing income or wealth for the majority of the country. My TikTok and Instagram feeds are sometimes littered with people showing videos of China’s cities lit up with evening light shows with captions like “THIS IS A THIRD TIER CITY IN CHINA AND ITS MORE FUTURISTIC THAN ANYTHING IN THE U.S.” Such flashy scenes are seductive, but also aren’t very representative—there are so many small and medium-sized cities in China with widespread unemployment, areas of disinvestment, poverty and regions entirely excluded from the boom in certain manufacturing sectors China is seeing. This is not unlike the geographic divide in the U.S. between left behind regions and superstar cities that many see as fueling the rise of Trumpism.

Having a more balanced view of the current situation in China, both its strengths as well as its continued frailties, is important for policymakers in the U.S. Too often, media and policy discourse alternates between extreme views: China is on the verge of collapse or it is about to overtake the U.S. in every possible way. Understanding where China is ahead (sectors like EVs, manufacturing, materials, rare earths) and where China lags the U.S. (enterprise business services, stock market, trust in its monetary institutions, and lack of appeal as a destination for international immigration and education) would help assuage the current myopic focus in the U.S. on “winning a race of China” where the goals or metrics of victory have never been clearly enunciated. In order to stay competitive, the U.S. can focus on its own strengths and advantages, such as its lead in higher ed and its appeal as a global destination for high-skilled workers. Instead, the Trump administration seems intent on destroying any of those advantages, all in the name of pursuing some romantic and outdated view of American manufacturing from the early 20th century.

Wang, Jia, and Liu, Bainian bianju 百年变局.

https://www.guancha.cn/JinCanRong/2019_07_29_511347_s.shtml

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/19/us-china-talks-alaska-biden-blinken-sullivan-wang

https://www.cnn.com/2023/01/31/economy/china-local-governments-basic-services-debt-crisis-intl-hnk/index.html

https://www.npr.org/2025/04/01/1241995527/chinas-global-electric-vehicle-boom

https://www.cnn.com/2024/04/24/business/china-ev-industry-competition-analysis-intl-hnk/index.html