Playing the "hukou card"? China's rural option for stimulating the economy

Are Hukou reforms on the table at the upcoming 3rd plenum? Removing restrictions on rural migration would stimulate the economy, but it also comes with significant costs and risks.

Reforming the hukou system entails additional costs in the form of local expenditures on public services, which thus has to be weighed against the likely economic boost that would ensue from enhanced labor mobility, consumption and investment in real estate sectors.

Some observers have noted hukou reform may be on the table at the upcoming 3rd Party Plenum in July. At the very least, some experts like Liu Shijin call for increasing subsidies and public services for newly arrived migrants or farmers in cities, according to recent post by The East is Read in which they argue that “In the long run, settling rural migrant workers in cities does not increase the public fiscal burden. Rural migrant workers settling in cities will enhance urban economies of scale and consumption capacity, expanding the tax base.” Announcing further relaxation of hukou policies could also stimulate the ailing property sector. China’s economy has still been driven by investment at the expense of consumption, as economists like Michael Pettis have long argued.1 The gap between China’s wealthy cities and rural hinterlands is a key factor in this (as well as decades of government policies favoring export-led growth). Rural dwellers are less able to enter property markets or participate in urban consumption. Unleashing a new wave of migration could help fuel domestic consumption, and could counterbalance some of the pressure on working population from demographic decline in the coming years. But its not that simple—more official urban residents mean increased expenditures on urban social services. And given many of China’s local governments are facing debt and bankruptcies, this money has to come from somewhere, and it would probably come from central government transfers.

Despite China’s massive urbanization and its plans for further urbanization to reach the rate of 80% (currently just over 60% officially)2 urban population (considered a “developed” country threshhold), the country’s 户口 hukou system has remained a significant obstacle to labor mobility. While limits on actual migration were lifted in the 1970s and 80s, all Chinese citizens have to be registered to a specific jurisdiction since the system’s beginnings in 19583, and many villagers are still classed as “agricultural”.4 Reforming the hukou system entails additional costs in the form of local expenditures on public services, which thus has to be balanced against the potential benefits that would ensue from enhanced labor mobility, a boost in consumption and real estate sectors in certain cities.Many of China’s rural residents are essentially trapped in place, unable to obtain permanent residence in top cities, and either confined to permanent “floating population” status. As Scott Rozelle of Stanford has pointed out, rural areas have inferior education and healthcare, a serious obstacle to economic mobility for 35% or more of China’s population (roughly 500 million) that remain officially rural.5

In recent years, however, a number of cities and jurisdictions in China have begun removing some of the restrictions on hukou application. In 2014, the National New-type Urbanization Plan (2014-2020) was released, which among other goals called for closing the gap in urban social benefits between urban and rural locales, with calls for unifying rural and urban hukou status, and laid out guidelines for small county towns and cities to : a.) Comprehensively relax restrictions on settlement in established towns and small cities., b.) Orderly relax restrictions on settlement in medium-sized cities (500,000 to 1 million), c.) Strictly control the population size of megacities (5 million+).67

Yet, as scholar Kam Wing Chan points out, the gap has actually widened since. Whereas the population residing in urban areas reached 63.9 % in 2020, 45.4 % had an urban hukou. The difference of 18.5 percent broadly represents the percentage of migrants living in urban areas without an urban hukou, often referred to as the “floating population” or liudong renkou.8 By 2020, this floating population has increased to 376 million, from 221 million in 2010.9 Hukou reforms have also been uneven (see below)—cities relaxing policies to attract college graduates of elite universities, for example, doesn’t help the majority of farmers or migrant workers. Restrictions on residence in smaller cities (i.e. county towns, and other cities) have generally been relaxed, but the largest and more competitive cities remain restrictive.

Recent Hukou Reforms

When we talk about “hukou reforms”, we have to be clear what this means—not all hukou reforms are the same. There are a host of benefits and restrictions bound up with the household registration system from land and housing rights to education and healthcare. Reforms can reduce barriers in some of these domains, while leaving others. Just to start, here are a few types of reforms seen across different jurisdictions, further explained below (not a complete list, but a general summary).

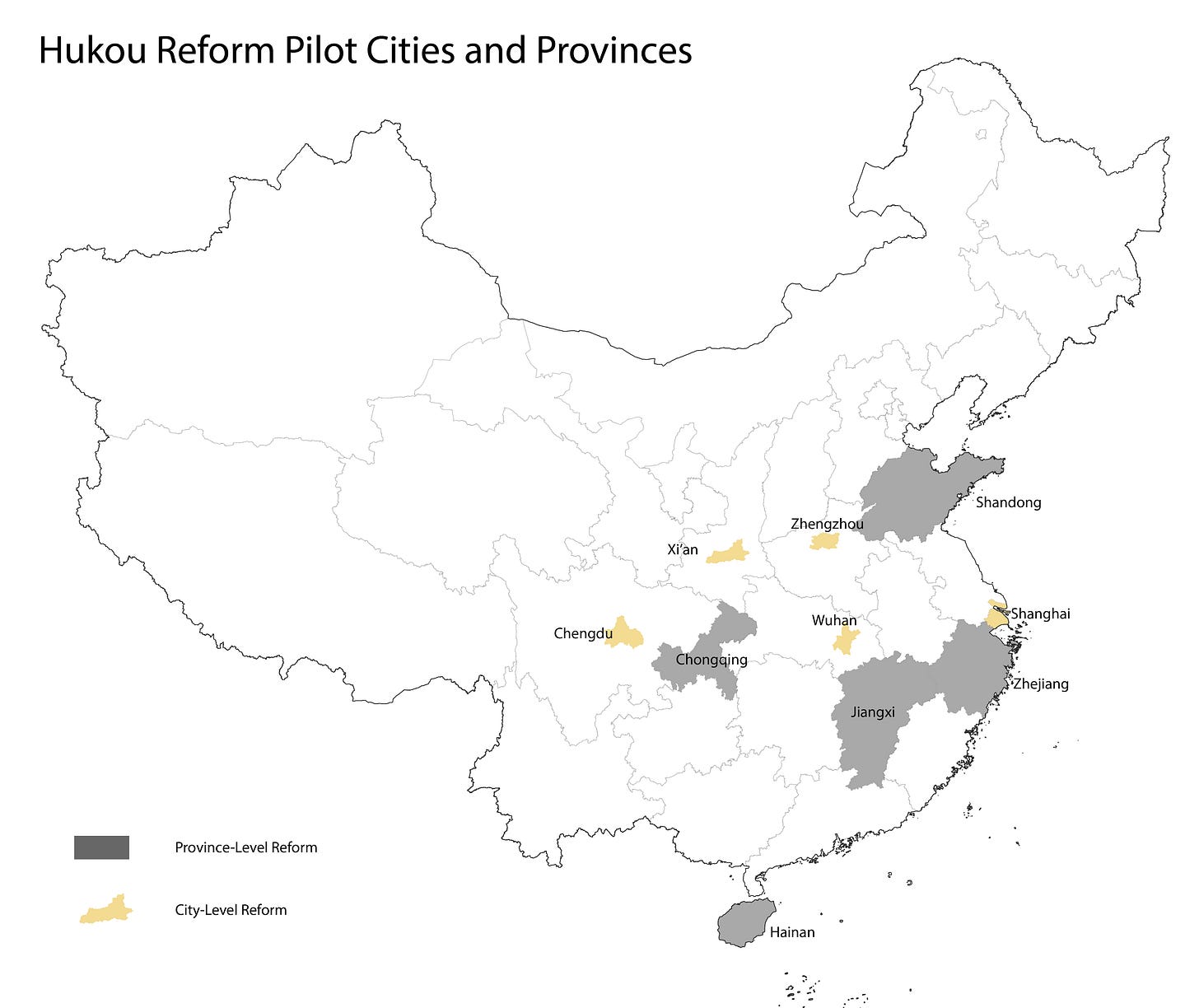

While some provinces and secondary cities have been relaxing various aspects of household registration policy over the past few years, the process has been uneven. Smaller less competitive cities, eager to attract more workers and investment in competition with other cities, have generally been more eager to roll back residency requirements (see the case of Zhengzhou, Henan’s provincial capital). The top-tier cities, like Beijing, Shanghai and many others, remain fairly restrictive to obtaining permanent residence but have generally tried to facilitate talented young graduates of their universities to stay beyond graduation— last year, Shanghai made it easier for graduates of its universities to obtain hukou status.10

Reducing barriers on rural residents to settle in urban areas of one jurisdiction: as many familiar with China’s administrative system know, “cities” are really often large regional areas including both urban districts 城区, and largely rural counties 县.11 I wrote something on this for the Atlantic back in 2013, but its still something many people have a hard time grappling with since China’s definition of a city is quite distinct from the U.S.. For the purposes of hukou, a city may allow rural residents in counties under that city’s jurisdiction to obtain residential status in the city, or to transact rural residency rights for lease in exchange for renting or obtaining housing in the central urban areas—this in essence, is a relaxation of rural-urban migration between core and periphery of particular cities.

Land Exchange (sometimes called 地票 dipiao), which has been tried in Chongqing since 2008 , is one way to help achieve this, by giving rural residents the ability to legally lease their village land (defined in China’s constitution as communal village property), in exchange for receiving residency in an urban district—crucially peasants may prefer to keep the right to their rural land as a form of insurance, while settling in urban areas.

Ending distinction between agricultural and non-agricultural: Because most prefecture-level cities diji shi 地级市 in China administer predominantly rural counties in addition to their core urban areas, ending distinctions on “agricultural” 农 between ”non-agricultural” 非农 status within a jurisdiction effectively allows migrants from a county to settle in a county town, or move their residence more easily between a county and a prefecture-level city with jurisdiction over that county. But that doesn’t necessarily mean just anyone from neighboring jurisdictions can move and obtain a resident permit in that particular city.

Relaxing restrictions on elite graduates to attract talent: Beijing and Shanghai are home to some of China’s top universities, attracting the most talented from across the country. While these cities are the most restrictive in terms of granting hukou, those with stable jobs and income and school attendance at elite institutions in these cities usually have a leg up in obtaining permanent residence there. Similar initiatives have been tried in Xi’an, Chengdu, Wuhan, Changsha and other provincial capitals, which are in a competition to attract talent, with burgeoning tech scenes and lower housing costs than the first-tier coastal cities.12

Provincial Relaxation: When hukou policies are relaxed at a provincial level, it generally means cities across the province may relax rules for rural residents to obtain residency in most cities throughout a given province. For example, in 2023 wealthy coastal Zhejiang province relaxed rules for hukou for every city except its capital Hangzhou.13 Shandong in 2014 relaxed restrictions on city residents obtaining residence in other cities in the province (except for Qingdao and Jinan).

While local jurisdictions have already been experimenting with their own reform policies for at least a decade, prospects for further reform of the hukou at the national level cannot be discounted. Yet, it is unlikely that the system will be totally dismantled in one fell swoop. The Party-State has been ever wary of unleashing uncontrolled migration to cities that might lead to slums, exacerbate housing prices in top cities, or upset the rising urban middle class which has become one of the Party’s key bases. Jeremy Wallace of Cornell refers to this as “urban bias”.14 Hukou reform also entails costs as well as benefits (some estimates of 1.5% of GDP annually to support hukou reform, but McKinsey in 2009 put this estimate at 1.5 trillion RMB a little over 1% of China’s total GDP currently, around 126 trillion RMB (17 trillion USD). This number didnt’t sound difficult to achieve in and of itself particularly when China’s GDP growth was around 9 or 10%. But in the midst of the current real estate slump and economic downturn, city governments are tightening their budgets amidst the slowing property market and declining revenue from land leasing. Reforming the hukou system entails additional costs in the form of local expenditures on public services, which has to be balanced against the potential benefits that would ensue from enhanced labor mobility, a boost in consumption and real estate sectors in cities.

This report from 2009 estimated how much public spending would need to increase by 2025 to include all migrants in cities that are not their permanent residence(McKinsey Global Institute, 2009)

In this post I will summarize some of the main local pilots that have implemented in China in the last decade or so. Critically, the unfolding of hukou reform will vary highly based on the types of cities we are talking about, ranging from top-tier cities (i.e BJ, Shanghai, Shenzhen), to second tier rising cities (i.e. Chengdu, Xi’an, Wuhan), to even smaller municipalities, county-level cities, and county towns. The way hukou reform is carried out also has implications for the distribution and pattern of China’s future urbanization—relaxing controls in secondary cities could stimulate growth there, avoiding over-concentration of people and resources in a few “superstar” cities. In a totally “free job market”, however, people move to where the jobs are.

A summary of some recent reforms by jurisdiction:

PROVINCE OR DIRECTLY RULED CITY

Shandong (2014)15 China’s second-most populous province (100 mn+) issued a general opinion to lift rules on rural residents obtaining urban residency in cities and allowed urban residents in one city to freely obtain residence in other cities in the province—but the capital Jinan and Qingdao were allowed to maintain some of their restrictions. Specific implementation was left to city governments.

Jiangxi (2021) One of the first provinces to relax restrictions to allow rural residents settling in cities in the province to apply for hukou without being residence for a minimum period of time16

Hainan: (2022)17 The island province moved to end the distinction between urban/rural and create a unified island-wide system

Zhejiang: (2023) The coastal province began to remove most restrictions on hukou status is cities except for the capital, Hangzhou. “Both local and non-local rural migrants have unified standards for urban settlement. Migrant workers will be granted a hukou based on habitual residence”

Shanghai: granting Hukou status for university graduates (2021)18

MUNICIPALITY

Chengdu, Sichuan: The provincial capital of Sichuan has been one of the earliest and most experimental in efforts to allow rural residents to sell or lease their rural land use rights in exchange for obtaining urban residency. Chengdu has been part of a national pilot program since 2008.

Zhengzhou, Henan: September 6, 2022: “According to the "Implementation Opinions", anyone who has legal and stable employment or legal and stable residence (including rental) in the central urban area of Zhengzhou is not subject to restrictions on social security payment years and residence years. The person and his spouse, children and parents who live together can apply for urban resident household registration in Zhengzhou; residents who meet the migration conditions can migrate between urban and rural areas”19

Xi’an (2018): Made it easy for university graduates to apply for hukou by submitting degrees and other identity info online and receive their hukou in the mail, and attracted 750,000 new residents.20

In a future post I will outline a few scenarios for hukou reform in the leadup to the 3rd Plenum, ranging from the most dramatic (a total ending of the system) down to more likely scenarios for further incremental reforms, and how possible increases in social spending and other benefits would interface with the broader household registration system.

https://www.ft.com/content/879f5de7-cd9b-4987-9c2b-8b23cf0f3800

China’s 64% rate of urban population is based in population living in urban areas is different to “registered population” which was around 45% in 2020 (Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census [1] (No. 7) National Bureau of Statistics of China May 11, 2021)

《中华人民共和国户口登记条例》1958

While the term “hukou” 户口 is typically used in English media about the entire system, it is more precisely referred to in Chinese as huji 户籍 or “household registration”, which means every household and individual in that household has to be registered to a location, typically a place of birth or primary residence. Furthermore, within the jurisdiction you are registered in, many are classified according to agricultural 非农业 or non-agricultural 农业. Because most village or agricultural land is typically classified as “collectively owned” 集体用地, whereas urban land is classified as “state owned”, under the management of city governments or state-owned enterprises, the difference in Hukou status of agricultural/non agricultural also necessarily implies differences in rights to sell and transact land. Rural land is not typically allowed to be sold formally, although villagers can and do build houses and other structures on collectively owned land—such as so-called “urban villages” or 城中村

Rozelle, Scott, and Natalie Hell. Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise. First edition. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

State Council. 2014. “Opinion on Further Reform of the Hukou System” [In Chinese]. July 30. Accessed July 30, 2014. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-07/30/content_8944.htm

30. Accessed July 30, 2014. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-07/30/content_8944.htm; https://eastasiaforum.org/2015/01/13/chinas-hukou-reform-a-small-step-in-the-right-direction/

Chan, Kam Wing. “Internal Migration in China” Knomad Policy Brief 16 November 2021

Ibid.

https://www.csis.org/blogs/new-perspectives-asia/chinas-hukou-reform-2022-do-they-mean-it-time-0

While China’s administrative hierarchies are quite complex. for simplification purposes we can classify them into “directly ruled cities” (Beijing, Tianjin, Chongqing, and Shanghai), which are administratively equivalent to provbinces. Prefecture-level cities (地级市) are the next level and typically include provincial capitals and other large cities within the province—these cities typically govern a city region including a core urban area and surrounding counties. The next level are county-level cities (县级市)are essentially city-level units but functionally equal to counties in that they are administered under a prefecture-level city. Finally, there are county towns (县城)that administer counties. And below that towns 镇, and villages (乡 or 村) Some towns zhen 镇 can be larger than county towns in pop. but administratively lower—they may be large market towns or have significant industries but functionally lower in the administrative system.

https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1002002; https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_2045519

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-17/chinese-province-eases-rules-to-promote-common-prosperity?sref=uccUiNCE&embedded-checkout=true

Wallace, Jeremy L. Cities and Stability: Urbanization, Redistribution, And Regime Survival In China. 1 edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

https://eastasiaforum.org/2015/01/13/chinas-hukou-reform-a-small-step-in-the-right-direction/; http://www.shandong.gov.cn/art/2014/11/29/art_107870_62276.html

http://www.jiangxi.gov.cn/art/2021/2/23/art_396_3199760.html; https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1006887

https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2022/01-04/9644213.shtml

https://www.caixinglobal.com/2021-12-02/shanghai-offers-residency-rights-to-graduates-of-local-universities-101812935.html

http://henan.people.com.cn/n2/2023/0921/c351638-40578644.html

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-12/12/c_137668654.htm