Revitalizing China's Urban Villages through Community Gardening

The case of Shenzhen's "Sketch Action" 草图营造

In 2017-2018, I spent a little under a year at Peking University’s College of Landscape Architecture. I was helping to set up a collaboration between Harvard Graduate School of Design and the landscape architecture college at Peking University called the “Ecological Urbanism Center” which was going to focus on strategies for retrofitting Chinese cities for climate change and sea level rise. The collaboration itself was short-lived, cut short by disagreements between the university departments over funding (perhaps a harbinger of the broader deterioration of the U.S-China relationship)—but that’s a story for another day!

While based at the beautiful campus of Peking University I got to know a group of energetic and creative students of landscape architecture. The department is headed by the well-known landscape architect Yu Kongjian 俞孔坚, who founded the large firm Turenscape 土人设计, and has designed numerous flood-resilient sponge-city projects around the country and worldwide. 1 During their time as students at PKU, they built a small demonstration “rainwater garden” on the site of the college, adjacent to the Weiming Lake. This small project would eventually lay the groundwork for their practice.

In the summer of 2024 I caught up two of these students in Shenzhen, Huang Binling and Yuan Zhenyu. I hadn’t seen them since 2018 when they were still master’s students. Six years had passed, and two of them had move to Shenzhen and in 2019 founded a landscape architecture practice called Sketch Action 草图营造.

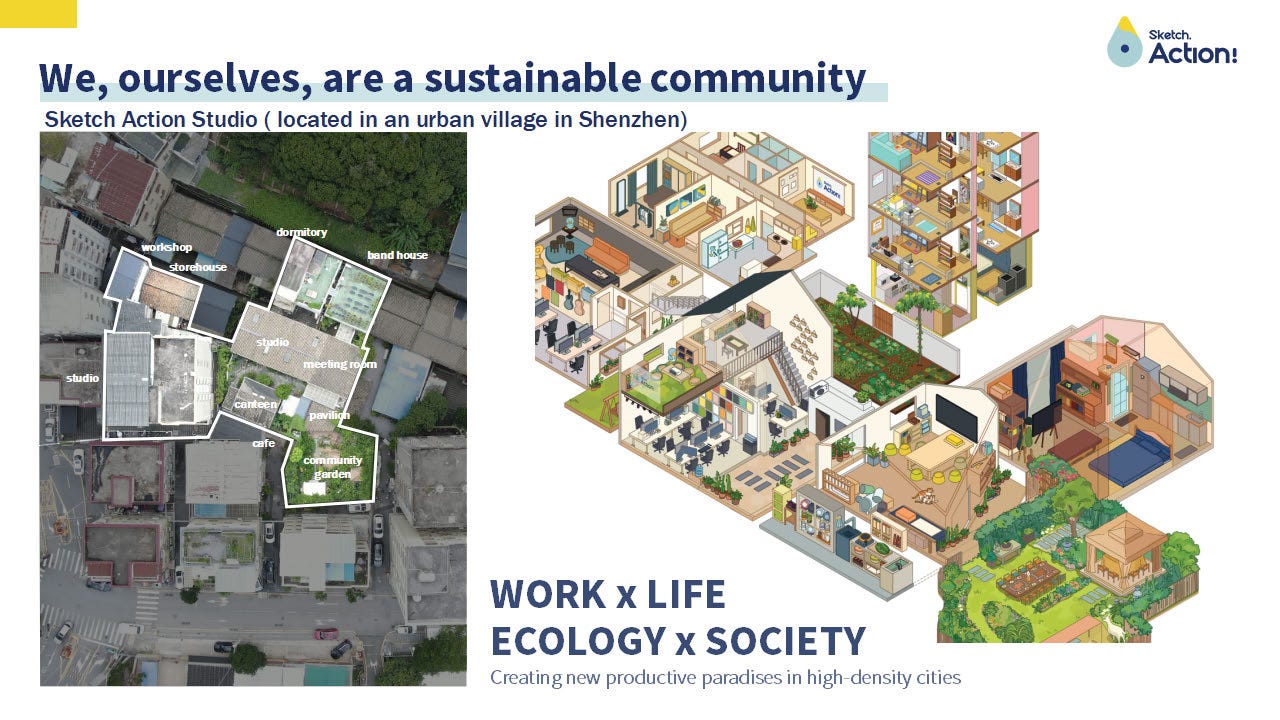

The two friends had been invited during Covid to move to an urban village in Shenzhen and set up their practice, and they had since made the village both their professional testbed as well as home base for them and their budding team of nearly 30 or so mostly youngish employees. Sketch Action’s practice is interdisciplinary, drawing on landscape design as well as participatory community-based planning. Sketch Action works alongside residents to co-create new spaces and help residents take a leading role in shaping and improving their own communities. The practice has also designed facilities for child-friendly and ageing-friendly communities throughout Shenzhen.

After an almost hour taxi ride from Shenzhen’s rail station I arrived at the Shangwei Arts Village 上围艺术村, located in the northern Longhua District 龙华区 of Shenzhen. There are 372 urban villages in Longhua District alone. Shangwei was an unassuming and modest village, ringed by small warehouses and repair shops. The village itself had been designated an arts and cultural village, and was home to a motley group of artists, sculptors, and other creatives.

The practice is dedicated to “community-gardening” as a form of regeneration of urban villages 城中村. Urban villages are a uniquely Chinese phenomenon, stemming from the confluence of rapid urbanization clashing with the existing dual land structure of Chinese villages/cities—village land is still classed as 集体 “collective”, with each villager entitled to collective ownership, often entailing rights in communal enterprises and right to build a house and farm. When Shenzhen urbanized, villages like Shangwei and many others were often able to keep their residential property, while farmland around the village was absorbed for urban development. Today, Shenzhen’s urban villages provide low-cost housing, vibrant street life and food. While many Chinese cities have been moving to demolish their urban villages, many of Shenzhen’s villages have become quite wealthy, undertaking their own property development and renovating homes, maintaining their “right to the city”.2 Villages in southern China, such as in Shenzhen and Guangzhou often have strong lineage organizations and corporatism, making them formidable forces in local politics.

I was greeted in the courtyard of the compound, which houses the studios, living space for the founders and some of the other architects, kitchen spaces. A video playing on the loop in the courtyard features Huang talking about his journey to Shenzhen and the idea behind the practice. I gave a presentation on my own research, followed by a conversation with the two founders and some of their staff.

Despite a downturn in the real estate and construction sector in China, Sketch Action had found a niche in small-scale village renovation projects. While each project is not hugely profitable (around 150,000 RMB, or $20k USD), they can do many small projects quickly, building up experience and scale. They have already completed over 100 community renovation projects in Shenzhen. The two young founders have already established a name for themselves in only a few years after graduating. As they told me, “we’re doing a small-scale approach so we are relatively lucky, this type of small scale revitalization is actually now taking off whereas the large-scale projects are slowing down.”

Huang and Yuan promote their approach as “community-led design”, borrowing from ideas about bottom-up urban planning and community governance in the West. They argue that their practice is “as much about governance 治理 as about design 设计. Although, even in the projects they have worked in, the commissioning entity is often the local village administrative committee, which is technically part of the state apparatus. Thus, the question of how much “grassroots governance” is really possible within China’s hierarchical administrative system is an open one. Huang and Yuan acknowledge this, but also state that they are commissioned by the local village authorities to undertake community planning, working with residents in the village on behalf of the local government, which lacks the capacity or understanding of community-driven design. So in this sense, they are consultants hired by the local village government to interface and work with the local population.

Their projects also span typologies from community gardening to public services. One of their projects in Shenzhen’s Window of the World neighborhood was built in a community with many foreign residents from 22 countries. Here, residents were selected by lottery to obtain small plots for farming vegetables, “including shared planting areas, gravel gardens, four-season orchards, herb gardens, bee and butterfly gardens, rainwater gardens, and activity squares.”3 At another project in the Huaiyayuan Community of Nanshan District, Sketch Action helped a community transform an empty paved area of a parking lot in front of the community into a diverse garden, and residents participated in planting and design themselves.4

In recent years, architecture and planning profession in Chinese cities have been discussing and promoting notions of “micro regeneration” or wei gengxin 微更新. Influenced by community-driven design in Japan, Europe, and elsewhere, the trend towards micro renovation comes on the heels of China’s massive urbanization, which has seen massive transformation of urban areas on a macro scale. As urbanization and growth slows, transforming urban neighborhoods through smaller-scale renovation is a more financially feasible and less disruptive approach to urban redevelopment than the wholesale demolition or chaiqian 拆迁 that characterized much of China’s rapid urbanization in recent decades.

I also spoke with Huang and Yuan about how their practice fits within evolving dynamics of local governance in China. Many media reports on China suggest the country has become more authoritarian during Xi Jinping’s presidency. And while Xi has undoubtedly centralized power at the central/national levels, at the grassroots level the story may be different. One thing the founders told me stuck with me—""the state increasingly wants local citizens to manage their own affairs if they can, the state wants this kind of grassroots appeal.” This also has to be seen against the reality of China’s local governments being on precarious financial footing since the ongoing real estate downturn drained a key source of revenue—land leasing. Local governments have limited funds for large-scale village demolition and reconstruction now, but small-scale community beautification efforts, such as the ones advocated by Sketch Action, are more in vogue now.

Do such small-scale efforts like the ones pursued by Sketch Action offer a future for China’s neglected urban villages and emptying rural areas? On the one hand, who can argue with the efforts to beautify urban villages through greenery and bottom-up design? To be sure, Shenzhen is one of the more progressive and liberal Chinese cities, so this too must be acknowledged. Sketch Action has worked in Wuhan but they acknowledged city government in Shenzhen is more open to these sorts of approaches than elsewhere. And of course, on their own such small-scale efforts will not be able to solve more intractable problems such as the emptying of the countryside, youth unemployment, or other problems of rural underdevelopment in China.5 But the visit to Shangwei Village and my conversation with Huang and Yuan were inspiring, that despite the fact of increasing centralization and authoritarianism at China’s top levels, there are counter-trends and alternative possibilities blooming at the local level.

https://www.turenscape.com/en/home/index.html

Al, Stefan, ed. 2014. Villages in the City: A Guide to South China’s Informal Settlements. Bilingual edition. Hong Kong : Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.; Wilson, Saul. 2023. “The Making of the Landless Landlord Peasant: Government Policy and the Development of Villages-in-the-City in Shanghai and Guangzhou.” The China Journal 90 (July):54–77. https://doi.org/10.1086/725664.

https://www.sketchaction.cn/10

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/-tpGNM-dh5S2Wc4fzDOjXg

Rozelle, Scott, and Natalie Hell. 2020. Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise. First edition. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press.

Thank you for sharing this. It would be interesting to follow how this kind of initiative spreads - or doesn’t - in other parts of China!