“In China, the combination of zoning and land leasing power within the same authority is the most important factor contributing to the monotony of urban districts.”

Over the last few months, whenever I told Chinese friends (or cab drivers) I am an urban planner, many responded with some version of the idea that “Chinese cities all look the same.” Of course, this is not entirely accurate—there are many cities with unique cultural heritage in China such as historic Beijing, Hangzhou, Xi’an etc. A cab driver in Hangzhou said, “Yes Hangzhou is nice but we just have West Lake, other than that it’s not beautiful.”

When it comes to modern urban development, the appearance and aesthetic of new urban areas is virtually identical in cities across the country. This is most apparent when riding high-speed rail— new stations are located on the edge of major cities, the better to serve as engines for new districts that were developed (or are still developing or half empty) on the periphery, and because land acquisition here is easier and cheaper than in central cities. Heading north out of Shanghai on the way to Beijing, you pass through new areas of Suzhou, Changzhou, Nanjing, Xuzhou, Jin’an—each of which is a forest of glass office towers and identical residential blocks.

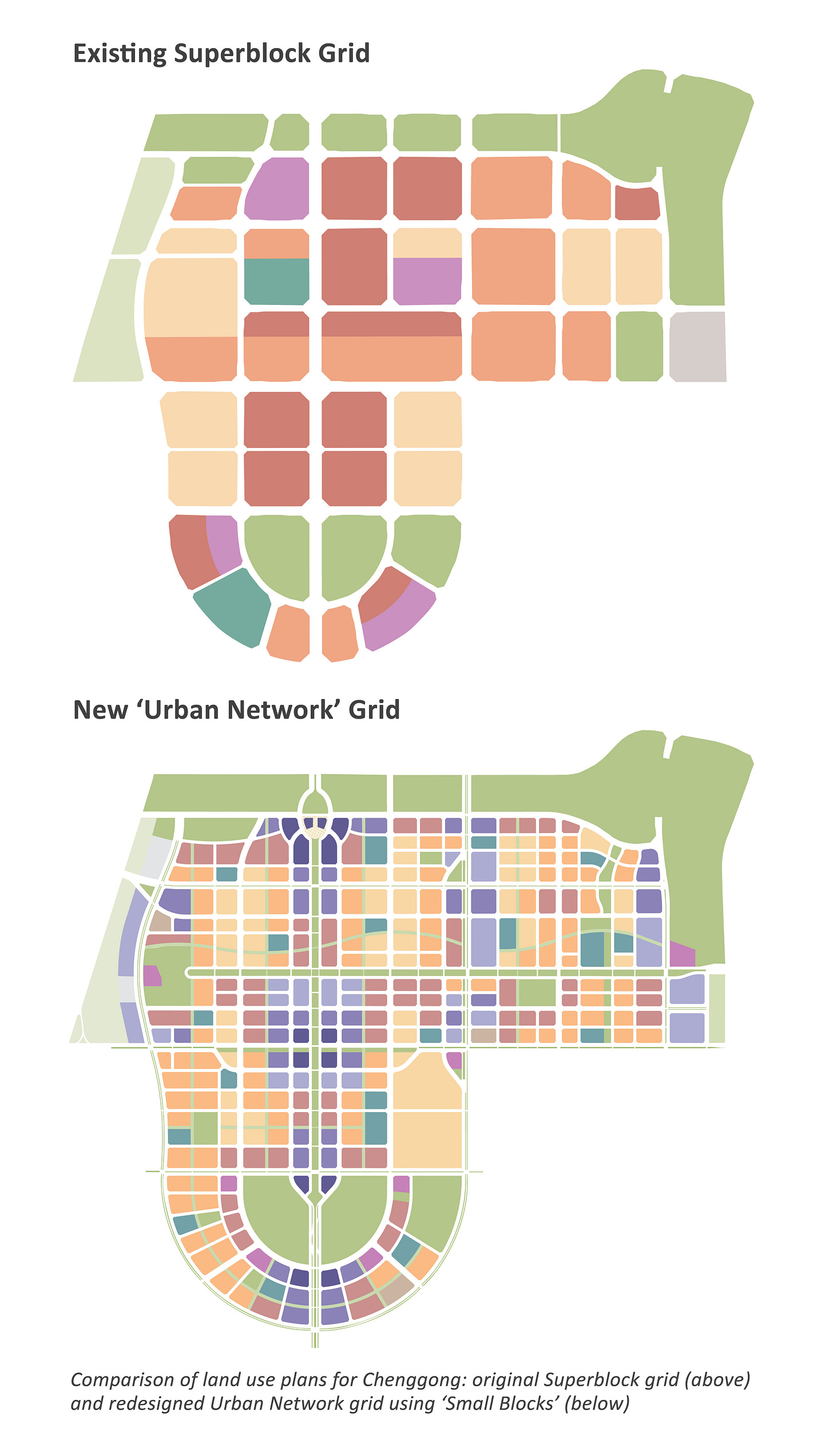

The notion that “Chinese cities are all the same” should be refined to specify the “new areas of Chinese cities” are all the same. Beijing inside the second road is the Beijing built by Ming Emperor Yongle: hutong alleyways, grey brick siheyuan, the cries of peddlers (albeit, increasingly rare). It’s an atmosphere that you can’t find anywhere else, and its why I always stay in this part of Beijing when I am in the city. But Beijing outside the second ring is indeed a monotonous sprawl of superblocks, gated compounds of state-owned enterprises, and highways too wide to cross in one traffic signal’s time. The pattern of superblocks originates in 1950s when Chinese cities were remade under Communist ideals of the 单位 danwei or “work unit” so that residents would live, work, eat, play, and receive all services from their employer, and never have to leave their work compound. But the “large block” pattern of urban development persists today. Why?

There are several reasons why contemporary Chinese urban development looks the same in most cities, but I think the most important ones can be summarized in this way:

A development model in which city governments lease large chunks of land to single developers (aka land finance, or 土地财政). In this system, almost all urban land is owned by the local government (a power only formally defined in 19881), which has both a.) power both to set planning guidelines (what we call zoning in the U.S.) AND to b.) lease that land for revenue. I believe this is the first and most basic reason for the monotony of Chinese cities, because even in areas that are built with supposedly innovative urban design principles (i.e. smaller blocks, TOD development, ample parks), you still get a monotony of building style due to the fact that large plots are all developed as part of a single development at the same time. If you have zoning (as in many countries) and smaller plots developed by many developers/builders, you can get the benefits of a more harmonized urban fabric while also having diversity of building character. In China, the combination of zoning and land leasing power within the same authority is the most important factor contributing to the monotony of urban districts.

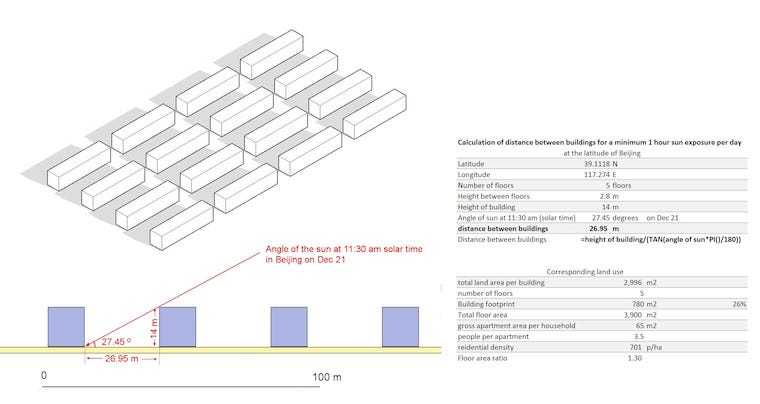

Standardized planning guidelines for density, FAR, setbacks for minimum unit sunlight, road width that make it almost impossible for developers to build anything besides a standardized urban block with often identical residential towers, often oriented to face South (optimizing sun/light exposure), but leading to the “endless slabs of tower” vibe you see in many Chinese cities.

National-scale real estate developers that operate across the country—many of these are state owned (China Construction, China Communications, China Merchants, etc), some private (Wanda, SOHO), partially owned by city SOE’s (Shenzhen’s Vanke), or local or local subsidiaries of national firms, but in general this nationalization of real estate means design templates and operational models became standardized across the country very quickly.

I. State Land Ownership and Land Finance

In the post Reform era, “1990s onward” such urban monotony is the direct product of a development model that has incentivized rapid urban development at all costs, including the cost of urban identity and culture. Otherwise known as tudi caizheng, this model’s essential logic has been city governments leasing off large chunks of land to developers who would build identical housing blocks. This system owes its general form to several aspects—the 1988 Land Management Law that stated municipal governments were the legal representatives of the state and could thus own land, and to the 1994 tax reforms which increased the central gov share of revenue and thus paved the way for cities to use their land resources to make up the revenue gap.

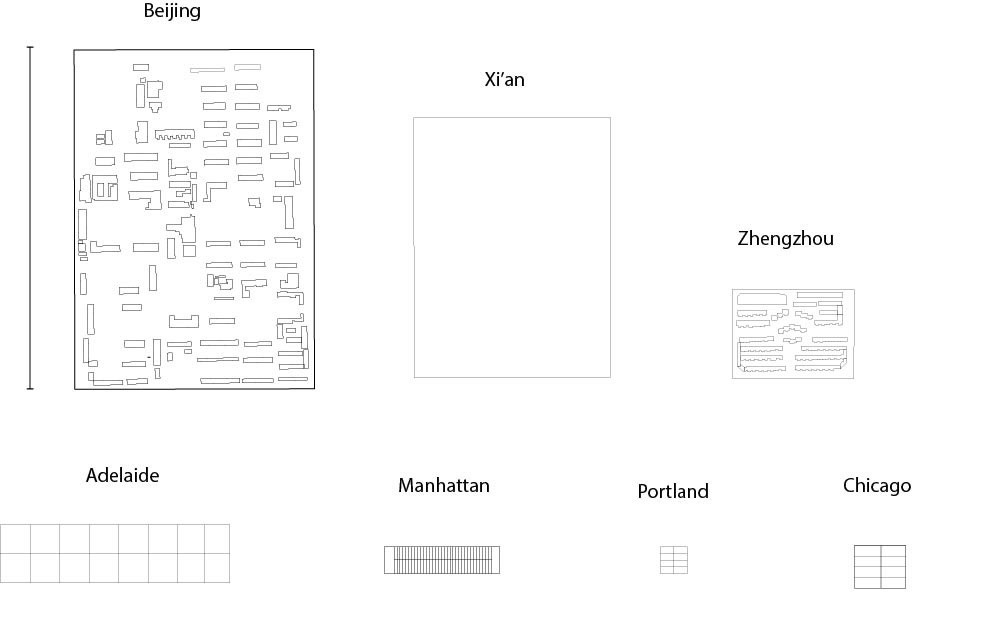

How does “land finance” contribute to the uniform character of Chinese cities? New areas of Chinese cities do not have the fine-grained urban fabric seen in successful vibrant cities (such as Tokyo, or Paris), or even in the older areas of Chinese cities. Urban vibrancy has a lot to do with density of businesses and diversity of uses. Diversity of land use and owners often leads to diversity of businesses and diversity of buildings. When land is sold en block to a single developer, the developer often maximizes profit by building the maximum allowable density. When this is repeated across an entire city, the results are depressing—monotonous tower blocks stretching on as far as the eye can see. There is density, but not necessarily walkable density or human-scale density.

II. Planning Guidelines

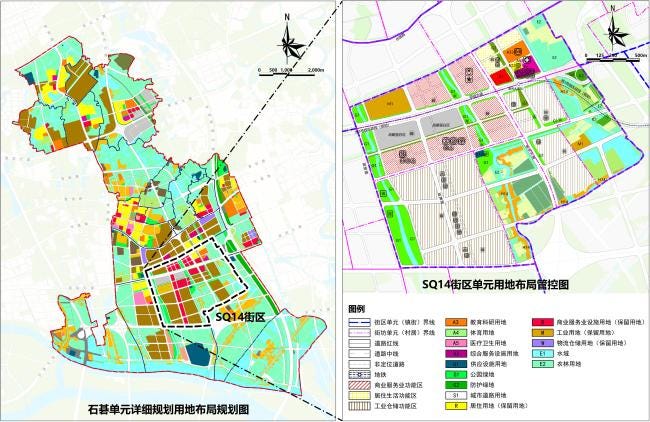

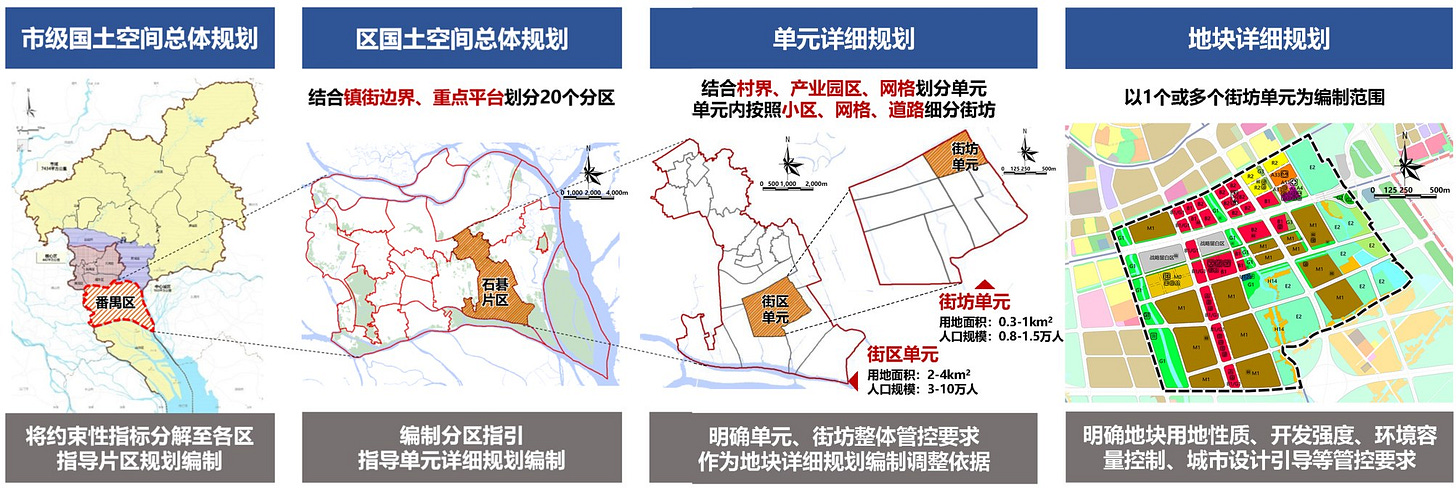

City planning and transport guidelines required massive streets and setbacks, leading to a form of zombie high-density but often un-walkable urbanism that you see in Chinese cities today. In China, almost all urban areas must go through a planning framework called 控制性详细规划 (regulatory detailed planning, or RDP). This is essentially a legal requirement for detailed land use by parcel, function, and density. The 1989 City Planning Act (Standing Committee for the People's Congress P. R. C, 1989) delegated power to municipalities in important functions of urban planning, ranging from plan-making to development control. Theoretically, this approach is not entirely different from the zoning model seen in Western countries, and in fact China’s current planning framework was mostly developed in the 1980s and borrowed extensively from Western planning approaches following the 1950s-1970s when China’s approach borrowed heavily from Soviet systems. However this process is also hierarchical in nature, reflecting China’s governance system. A general land use plan set at the city level and is then passed down to lower level districts and detailed unit plans (see diagram below).2

Another important planning regulation affecting urban form has to do with sun exposure, which dictates the spacing between buildings and constrains what is possible to develop on a Chinese block. According to a study by NYU’s Marron Institute, these regulations were set in the 1950s and mandated that “at least one room in each apartment receive a minimum of one hour of sunshine on the day of the winter solstice, December 21…The rule boiled down to a simple mathematical formula: distance d between buildings is determined by the height of building h multiplied by the tangent of the angle α of the sun on the winter solstice at 11:30 in the morning using solar time.”3

Evolution of the Superblock Typology in China

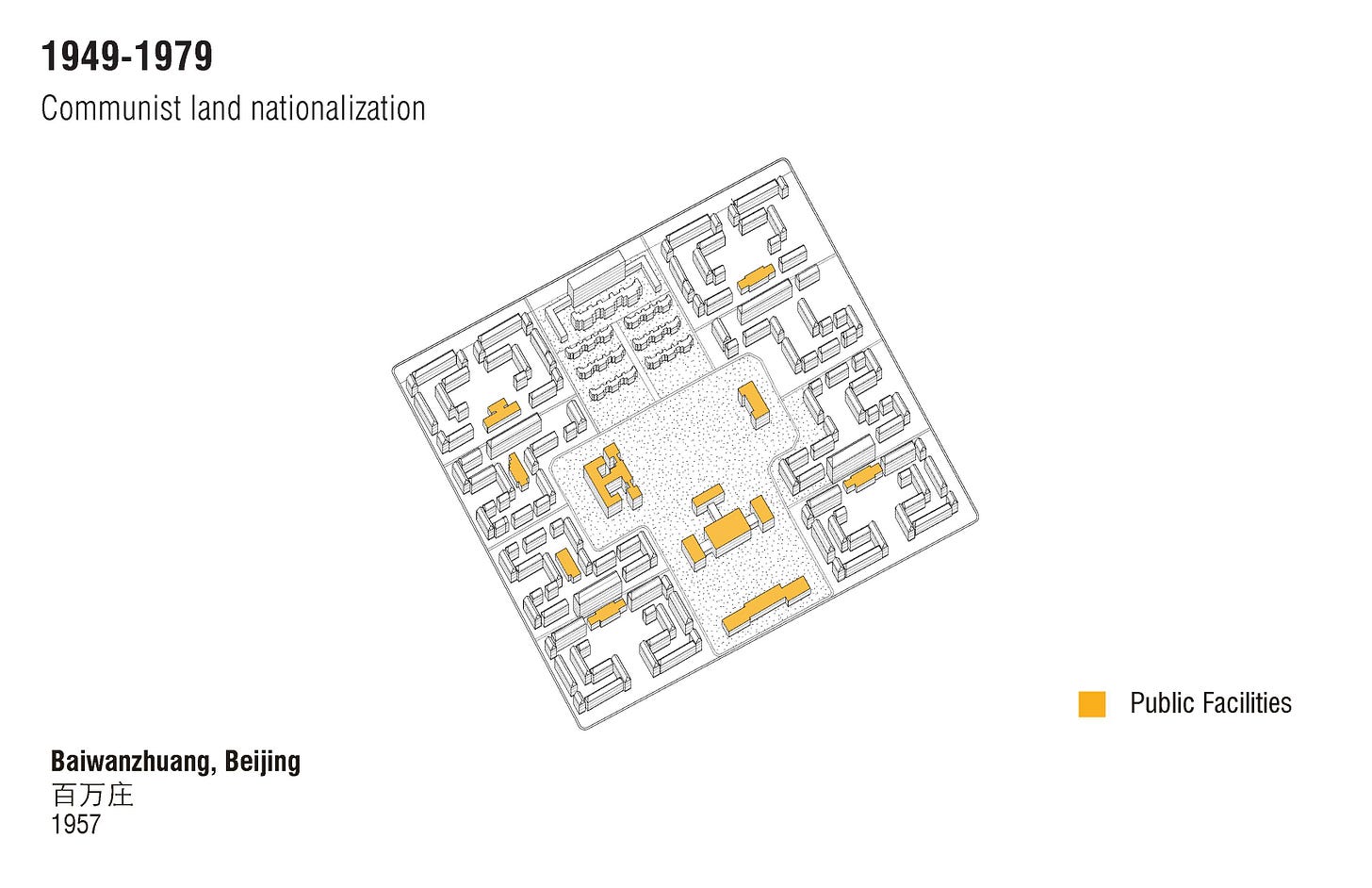

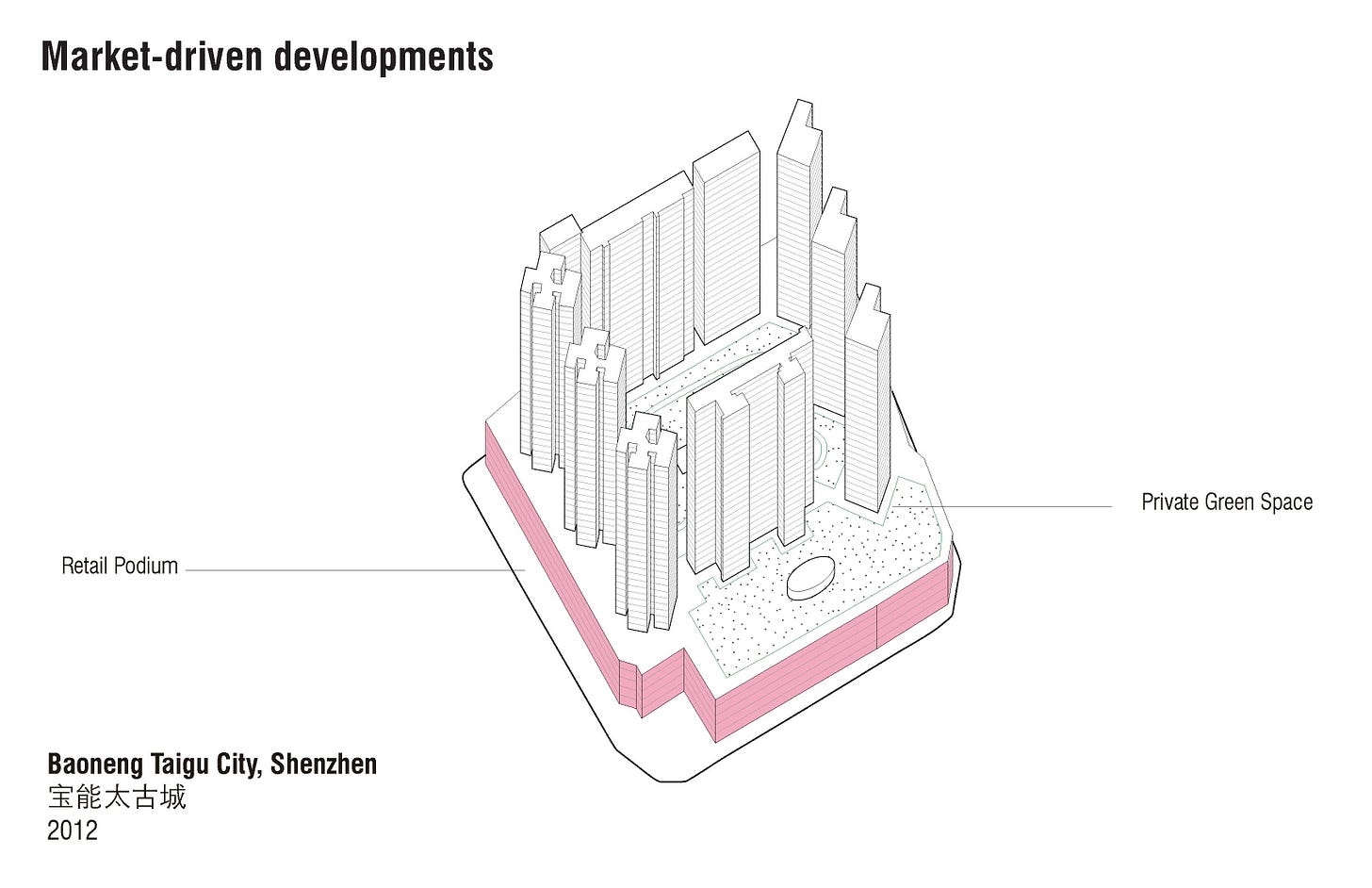

Gated neighborhoods have been an enduring feature of Chinese cities from Chang’an’s walled fang in the Tang Dynasty, to Beijing’s banners, to the work units or danwei of the early Communist period. Today, the enclosed neighborhood or xiaoqu endures as a basic unit of Chinese cities, albeit mostly in “market” form. Despite policies released in 2016 calling for opening up gated communities, gated residential compounds have endured as a consumer preference and spatial organization of local governance.4 This proved especially visible during Covid-19, when Chinese cities were able to enforce strict lockdowns by locking down specific neighborhoods. The following diagrams are taken from my 2017 Master’s Thesis at Harvard GSD on the Chinese superblock, Re-FORM. The first part of the thesis provided historical context of the evolution of the superblock in the PRC, from the early enclosed model Socialist urban neighborhoods to post-Reform commercial developments. Even as the form, density, and design of such neighborhoods has varied, the enclosed typology has persisted.

III. Nationalization of Real Estate Firms

The nationalization of real estate firms is another important factor in the uniformity of Chinese cities. Nearly every Chinese city has a Wanda Plaza, a SOHO (in top-tier cities), and they are more or less identical. In a manner unlike anywhere else in the world (that I’m aware), China’s developers operate at a national scale. In 2014, of China’s top 10 developers, 7 were state-owned enterprises.5 Some of these developers are centrally owned enterprises (China Merchants 招商, China Resources Land 华润, and Poly Group 保利集团, for example). Others, like Vanke 万科 and the bankrupt Hengda 恒大, began as local enterprises (Vanke is partially owned by Shenzhen’s government) but grew into national developers. The national scale of top developers in China likely stems from these firms preferential access to financing (state owned banks), political relationships, and other factors. Other countries like the U.S. also have national housing developers—think Lennar, a massive homebuilder in the U.S. But by and large, local real estate markets are dominated by smaller regional builders. According to 2023 report by a Chinese research firm on the real estate market state owned developers had strengthened their position. Compared with 2021, the top 10 real estate developers sales as a proportion of the top 500 developers had risen from 30% to 37% indicating increased concentration among top firms, as the sector has struggled following bankruptcies and China’s real estate downturn.6

"Top 500 comprehensive strength of real estate developers”: 7

China Overseas 中海

Vanke 万科

Poly Group 保利

China Resources Land (Huarun) 华润

Country Garden 碧桂园

Longfor 龙湖

China Merchants Shekou 招商蛇口

Gemdale Corporation 金地集团

Greentown China 绿城

Seazen 新城

IV. What is to be done?

China’s planners and officials are not oblivious to this issue. In fact, a friend of mine working as a researcher with a prominent design school in China described a nationwide research project currently underway to develop a system to monitor and identity the “essential qualities” 文脉 wenmai of townscape characteristics in major cities in China, and implement policies to try to retain or refurbish cities to maintain this “essential quality.” Of course, such an approach begs the question: can the ‘essential essence’ of a city be identified through computer vision or AI models, and if so, is it right or even desirable for planners to try to steer cities toward some “essential appearance”? This risks reifying the very sameness that it set out to correct, albeit in the name of maintaining a particular city’s essence. To say nothing of lived daily culture as an equally if not more important aspect of urban culture that will not be captured by AI models alone. This also begs the question of what sort of diversity in urban appearance is desirable: many of Europe’s beautiful urban centers have a degree of standardization in building typologies, facades, and styles that gives a sense of harmony and integration. The standardization of Parisian avenues, for example, dates to the mid 19th century reforms of Baron Haussmann, who bulldozed medieval slums to erect the boulevards lined by apartment buildings that now form the quintessential image of Paris. Cities like New York or Tokyo, meanwhile, have a more “organized chaos” approach where there is a great deal of diversity of building style and form, although certain common typologies do exist—think New York’s brownstone rowhouses, or Tokyo’s ubiquitous small/medium-sized apartment buildings.8 Whereas Paris and other European cities like Barcelona exhibit a high degree of coordination of building style, Tokyo and New York City are good examples of a mix of standardization and diversity. Chinese cities (particularly newly built district) suffer from an unfortunate degree of over-standardization while lacking space for the diversity of building facades and shopfronts.

Rithmire, Meg. Land Bargains and Chinese Capitalism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

新时期国土空间规划理论、方法与实践(二) 热带地理 ›› 2022, Vol. 42 ›› Issue (4) : 554-566. DOI: 10.13284/j.cnki.rddl.003475; 胡智行. 2021. 空间规划传导机制中的“刚”与“柔”——以上海崇明区为例. 城市规划,45(5):68-75. [Hu Zhixing. 2021. "Rigidity" and "Flexibility" in the Transmission of Spatial Planning: A Case Study of Chongming District, Shanghai. City Planning Review, 45(5): 68-75.

https://marroninstitute.nyu.edu/blog/markets-vs.-design-regulating-sunlight-in-pre-reform-china

Chiu-Shee, C., Ryan, B. D., & Vale, L. J. (2021). Ending gated communities: the rationales for resistance in China. Housing Studies, 38(8), 1482–1511. https://doi-org.libproxy.mit.edu/10.1080/02673037.2021.1950645

https://www.mingtiandi.com/real-estate/research-policy/country-garden-slips-to-6th-among-chinas-top-developers/

http://m.fangchan.com/industry/22/2023-03-23/7044251030703641147.html

Source: CRIC, Shanghai E-House Real Estate Research Institute 上海易居房地产研究院

Kuroda, Junzo, and Momoyo Kaijima. Made in Tokyo: Guide Book. Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co., 2001.

You see Chinese respond to their history.

Soon after China opened, the overwhelming emotion was shame. Areas of China were closed because the Chinese were embarrassed.

I was accosted by uniformed police, once for “disorderly photography” in Hanzhong, Shaanxi and once for paying too much for a small melon in Goat Home Mountain.

I paid the vendor a few cents for a melon. I didn’t haggle. Word spread how I had such wealth, I paid an exorbitant price without haggling. The police, driving a Beijing Jeep, stopped me from entering the outdoor market the next day. I was permanently barred from shopping there.

In Shanghai an early hotel was the Sheraton Hua Ting. City officials wanted ornate and fancy. Crowds gathered outside behind police cordons to watch, mouths agape, as elevators ascended outdoor walls.

At the request of city officials, the hotel installed so many indoor waterfalls that people had to shout to be heard. The waterfalls were soon removed

It would be useful to review “Seeing Like a State” by James Scott for insights. The centralized state wants legibility, which demands rationalization and same-ness. It is the unavoidable outcome of a system that demands control.