Xi Jinping's Archival Project to Rewrite Chinese History

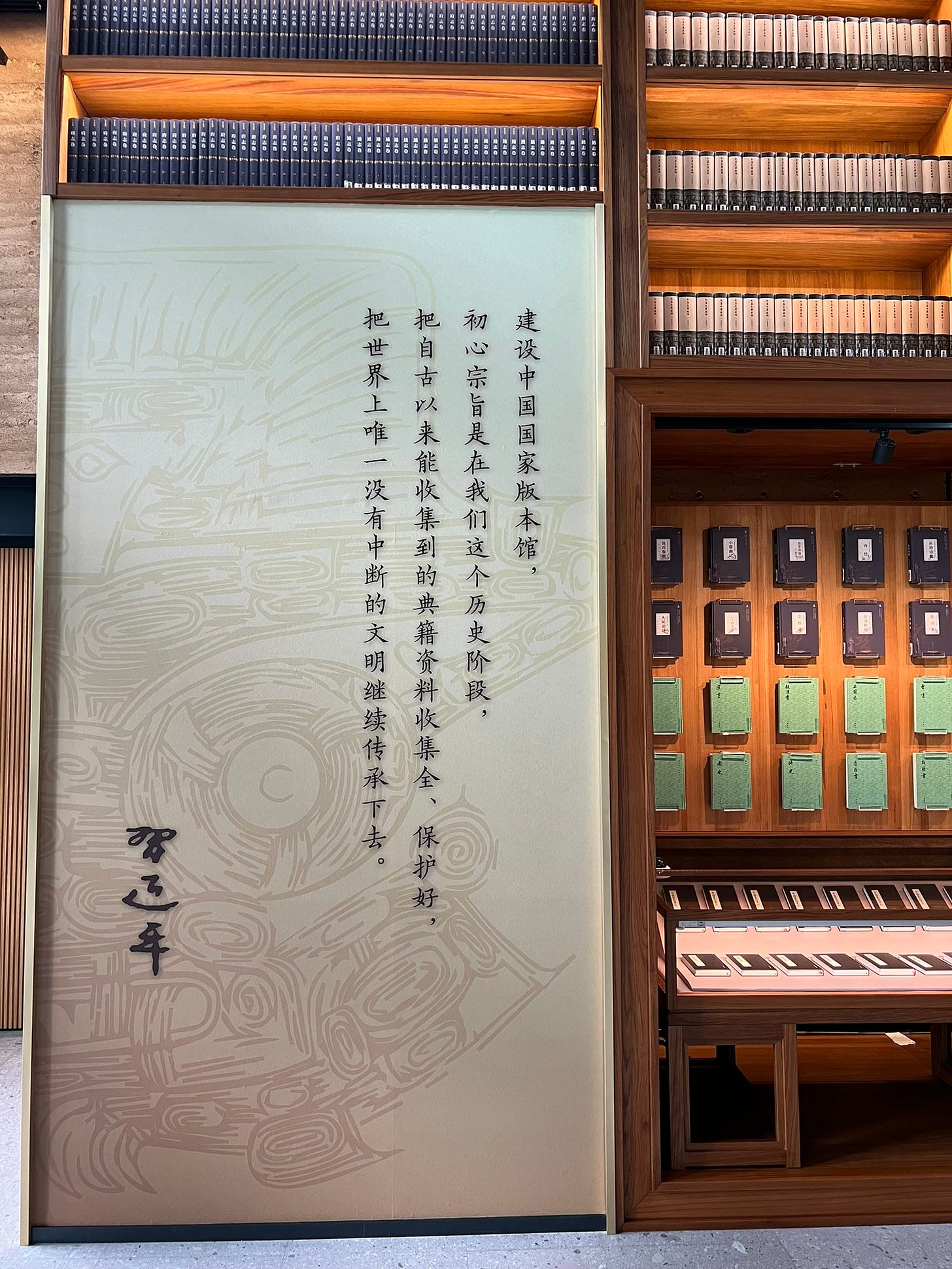

The National Archives of Publications and Culture is Xi's version of previous Imperial archival projects like Qianlong's Four Treasuries or the Yongle Dictionary.

“The new National Archives of Publications and Culture is designed both to hold copies of these very editions, and itself can be viewed as Xi Jinping’s own attempt to synthesize and curate Chinese history in a way that serves contemporary political ideology of the CCP.”

A “seed bank” of Chinese civilization: The National Archives of Publications and Culture 中华文明的种子库: 国家版本馆

Earlier, I wrote about a key cultural project begun under Xi that has not gained much attention—either in China or abroad. This post is a follow up after I had a chance to visit two/four of the branches this past summer.

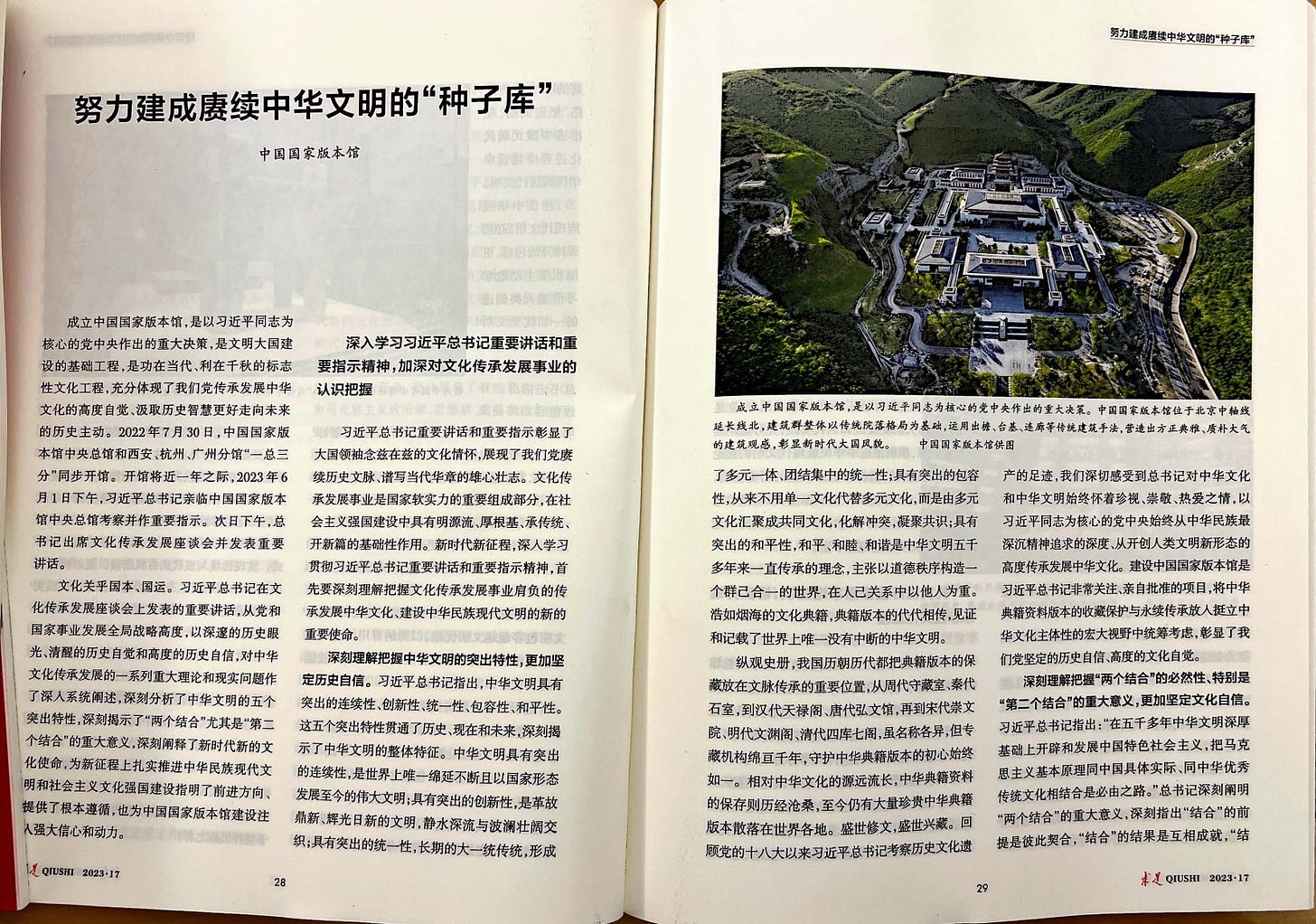

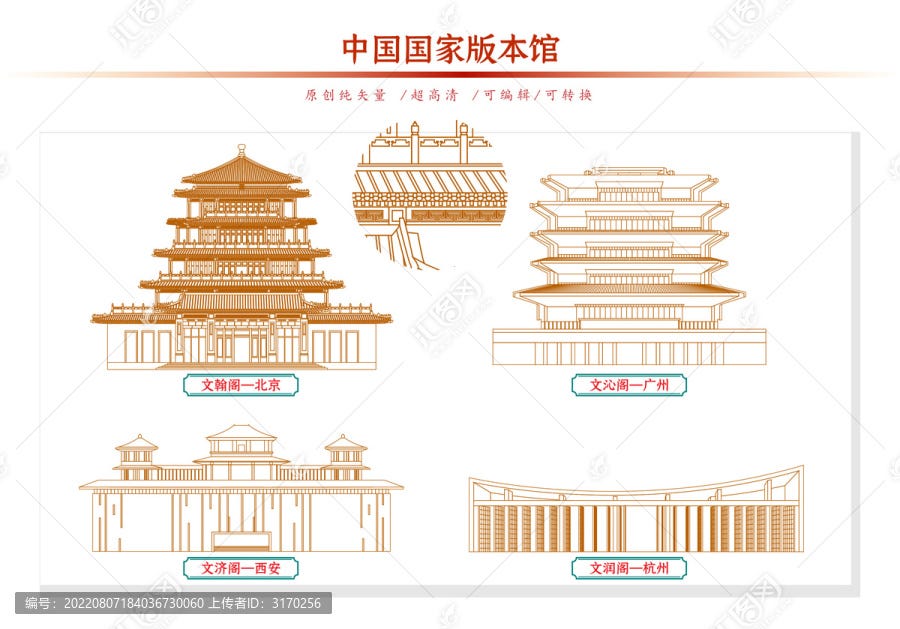

In 2019, Tsinghua University’s Zhuang Weimin (the Dean of the School of Architecture) received an invitation directly from the central publicity department of the CCP (中宣部) to participate in a competition to design the main branch of the new China National Archives of Publications and Culture 国家版本馆. The main branch is located in the mountains north of Beijing, directly on the city’s central axis. Unlike museums, which are often located in prominent locations and designed to attract the public, this is a different type of institution. It is remote, difficult to access, and focused primarily on archival and preservation work as well as serving as a “patriotic education base” for Party cadres and SOE employees. There are three other branches around the country: Hangzhou, Guangzhou, and Xi’an (with Beijing, each in one of the cardinal directions in the country). The system is described as a 1+3 cultural security system 文化安全体系, designed to safeguard China’s precious archives and artifacts. It is thus positioned as a critical part for Xi’s broader project of national rejuvenation and “cultural self confidence” 文化自信.

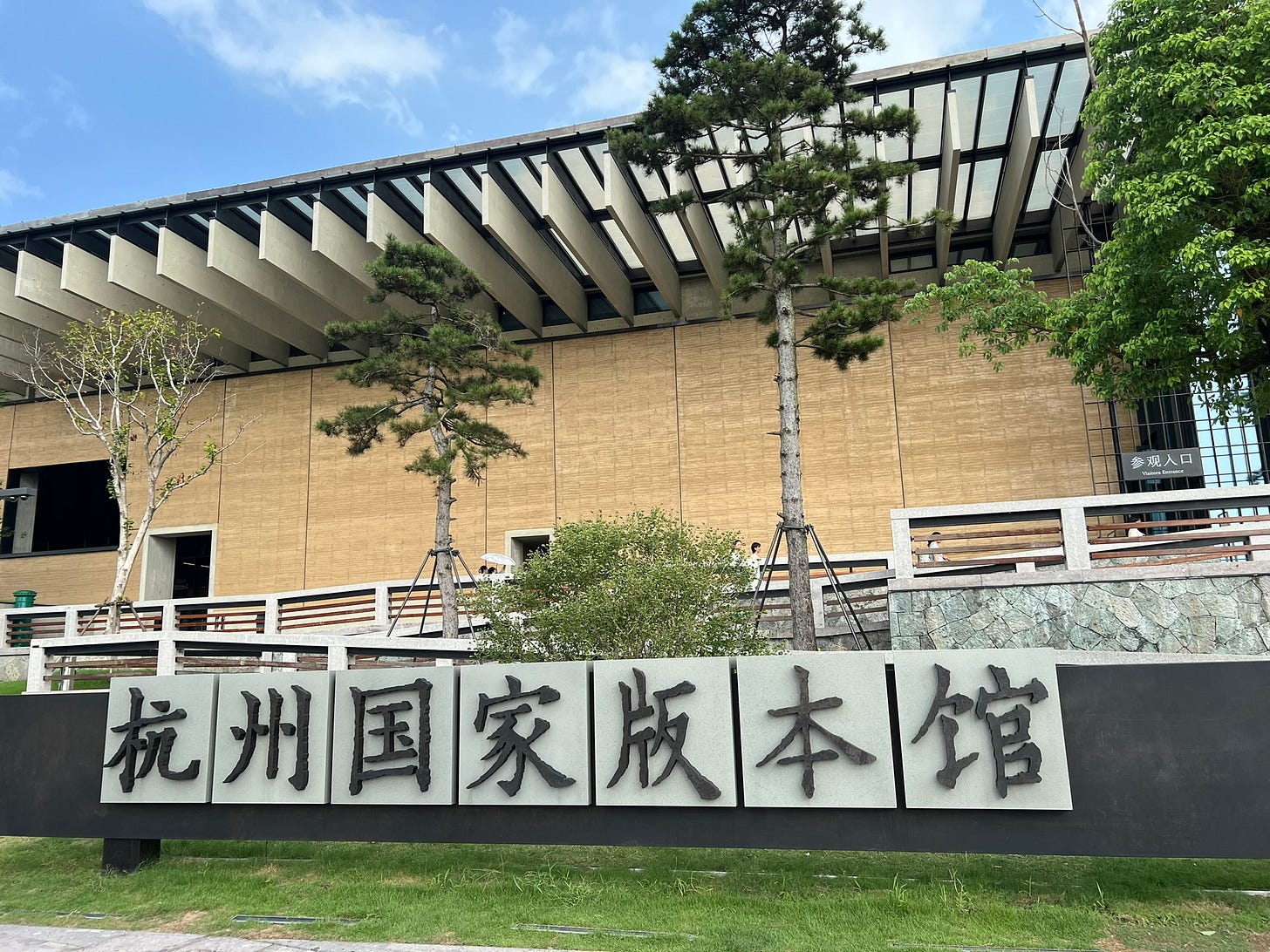

This past summer (2024) I visited two of the locations: Hangzhou and Xi’an. Only the Hangzhou location is currently open to the general public. The others are currently reserved for tours for 事业单位, essentially meaning govt or state-affiliated institutions. I was only able to visit the front of the Xi’an complex, which is located at the foot of the Qinling Mountains southwest of Xi’an.

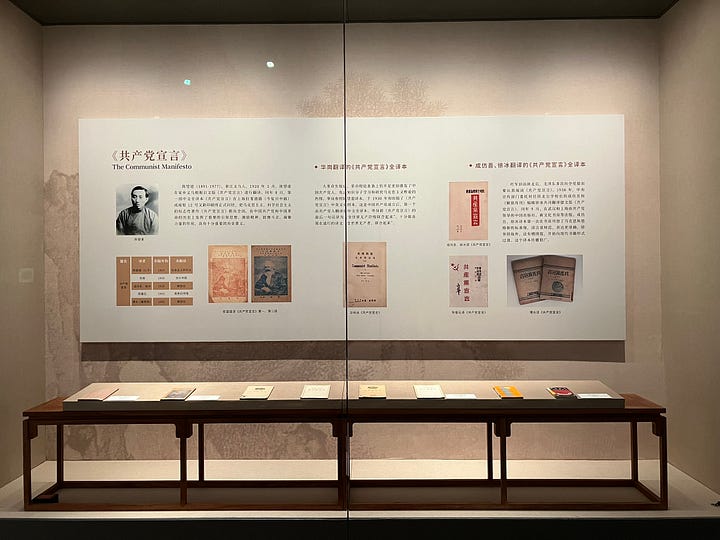

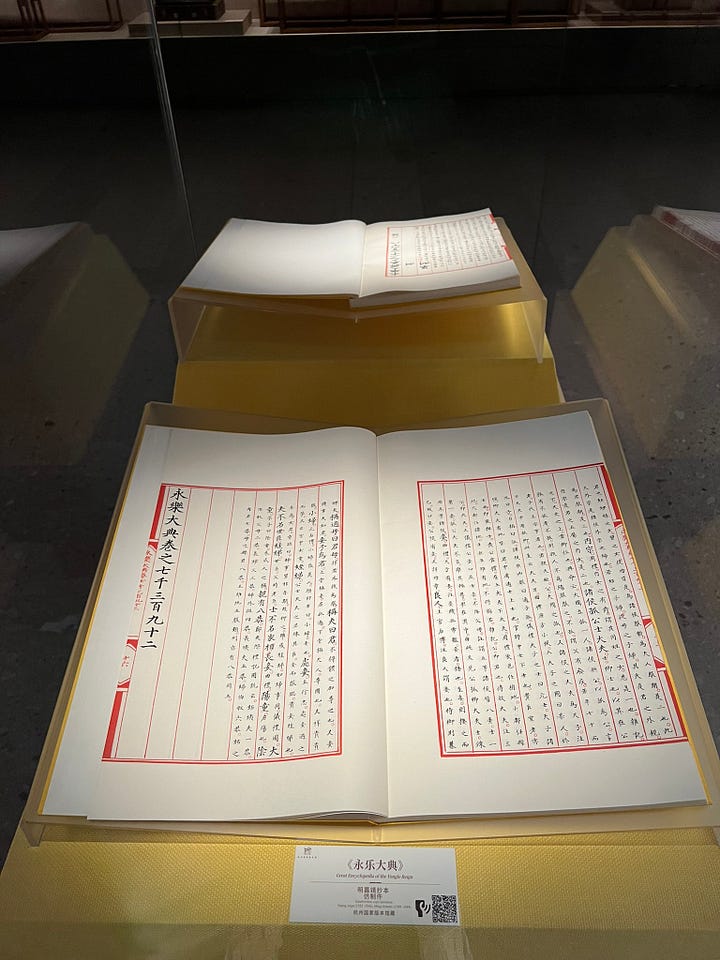

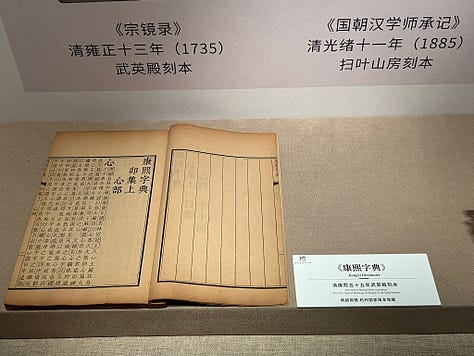

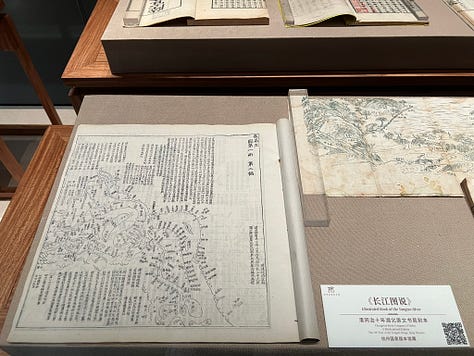

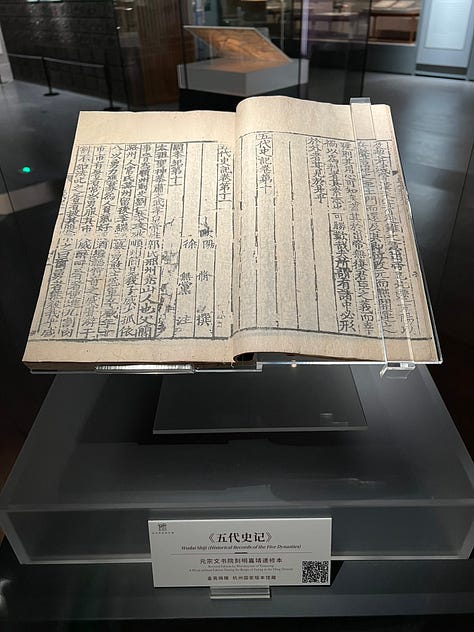

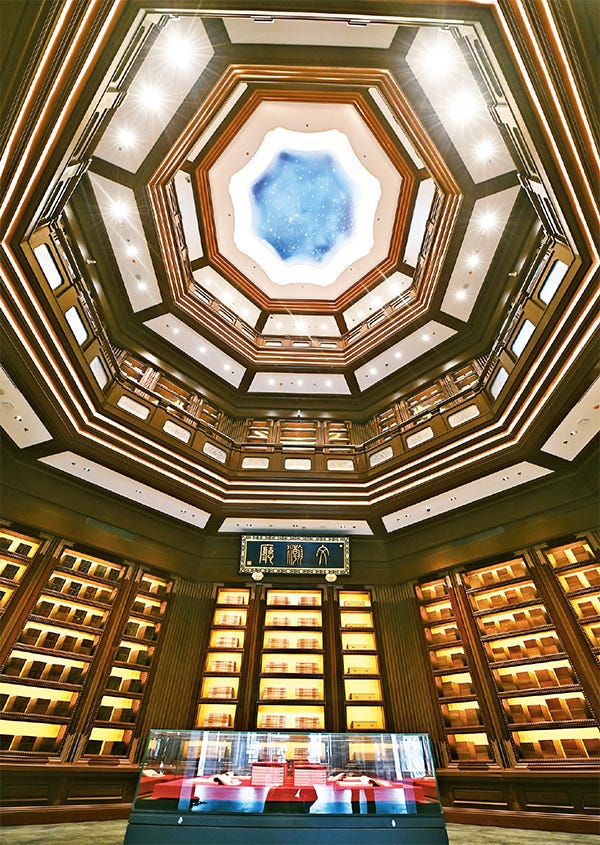

While the project has received little attention either inside or outside of China, I’m particularly interested in it as a reflection of official thinking about the importance of cultural heritage and “cultural self confidence” to China’s current governance model, and to the nascent idea of the “two integrations” 两个结合—a Party propaganda effort to claim Confucianism and Marxism are perfectly compatible, and always were.1 How does the archive project do this? In some cases, quite literally. For example, in the main exhibit of the Hangzhou branch, a copy of the Yongle Dictionary 永乐大典 (completed originally in 1408 during the early Ming dynasty) is displayed alongside another exhibit on the history of the Communist Manifesto. In the Beijing branch, the main exhibit in the Wenhan Pagoda 文瀚哥 is “The Light of Truth - Classic Archives Exhibition of Marxism Localization and Modernization in China.” In the same room are copies of the Siku Quanshu 四库全书 (the Four Treasuries), Yongle Dictionary, and The Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China (completed in the Qing period under emperors Kangxi and Yongzheng). All of these encyclopedic editions were themselves scholarly and political projects of editing and curating history overseen by particular emperors, often with the goal of sanitizing history or erasing unwanted details from official records—in the case of Qianlong’s Four Treasuries, early conflicts between Han and Manchu that were seen as sensitive to the ruling Manchu class.2 The new National Archives of Publications and Culture both holds copies of these very editions, and serves as Xi Jinping’s own attempt to synthesize and curate Chinese history in a way that serves contemporary political ideology of the CCP.

In the past, these imperial “publications” were not seen as part of a continuous “canon” of Chinese literature, but this is indeed the implication of the exhibition and curation strategy of the NAPC.

“In the main exhibit of the Hangzhou branch, a copy of the Yongle Dictionary 永乐大典 (completed originally in 1408 during the early Ming dynasty) is displayed alongside another exhibit on the history of the Communist Manifesto.”

Hangzhou Branch 杭州分馆

The Hangzhou Branch, designed by Pritzker Prize winning Hangzhou-based architect Wang Shu 王澍 a stunning ensemble of architecture and landscape. It’s the only branch of the four currently open to the general public. Located in the suburban Liangzhu area of Hangzhou, the Hangzhou branch emphasizes Jiangnan style architecture and bibliographic culture. The Jiangnan Region, China’s most prosperous area in late imperial times and the crucible of literati culture, is a natural place to have a museum on China’s bibliographic and literary culture.

The main exhibit of the collection focuses on the bibliographic history of China and the region, and the numerous editions of important works: histories, maps, archives, and other documents. Interestingly, a copy of the Yongle Dictionary 永乐大典 is a highlight of the exhibit, and is placed in close proximity to an exhibit on the evolution of the Communist Manifesto. The implications are obvious-that the Communist Manifesto should not be viewed as in a category separate from important documents of China’s imperial past, they are both “editions” 版本 that reflect important moments in China’s history.

Xi’an Branch 西安分馆

The Xi’an Branch was designed by well known Xi’an architect Zhang Jinqiu 张锦秋, who has designed numerous cultural buildings in the city such as the Sha’anxi Provincial Museum 陕西省博物馆 and the recently completed Qin-Han Pavillion of the Sha’anxi Provincial Museum 陕西省博物馆秦汉馆. The location of the Xi’an branch is also interesting—note in the above image the central axis of the archive is aligned with the mountain peak behind it—a so-called “dragon’s vein” or longmai, in the traditions of Feng Shui. The area is also perhaps not coincidentally where illegal villas were demolished in a 2016 scandal that brought down much of Xi’an and Sha’anxi province’s top leadership. Xi Jinping, when visiting the area remarked, “let this be a warning that cadres must always protect the Qinling mountains.” The location of the archives built nearby these demolished villas, an investigation personally overseen by Xi, is yet another reminder of the power of the central state over the commercial interests of local officials.

Since I was only able to visit up to the front gate of the Xi’an branch (visits are currently limited to official state organs or 事业单位), I must rely on other news and reports of the site for insights into its content. The Xi’an branch is focused on important materials relating to the rich history of the area as the site of China’s earliest capitals (Chang’an in the Qin, Han, and Tang Dynasties) as well as the role of Xi’an as a gateway to the silk roads. I did speak to a friend who had visited, someone who works in the cultural industries in Xi’an, and he said the curatorial strategy was a bit sparse. “The project came out of nowhere, from the very highest reaches of the Party all of a sudden. But there hasn’t been a lot of thought into what it should be—a museum, a place for preservation? It’s still being worked out.” This might explain the current limited access to the Xi’an and the other two branches.

Conclusions

The ideological aims of the National Archives of Publications and Culture are fairly straightforward to anyone with even a cursory understanding of Chinese Marxist ideology, and the history of China’s imperial archival traditions. The project’s own reference to these earlier projects makes the connection even more clear. The NAPC obviously doesn’t include sensitive aspects of China’s recent history, but that is not unique—most state-backed institutions in China do not. Rather than censorship, the primary goal of the NAPC is to bolster the idea that the Communist Party is the rightful and legitimate inheritor of China’s ancient civilization, and to bridge the gap between the Party’s own ideas and history and the history of China’s imperial traditions—particularly in the world of publications.

Whether or how effective this project (and other related efforts) will actually be in rewriting China’s history remains to be seen. As Ian Johnson has written of China’s “underground historians”, there are many grassroots efforts to keep aspects of China’s history alive beyond the reach of the Party State—in the form of small groups of dissident archivists or digital archives.3 Can a project like the NAPC really transform the understanding of history with a vibrant, albeit heavily suppressed, online sphere?

As with much of China’s existing censorship and information control apparatus, the State knows such efforts will not reach everyone. But they don’t need to. By the financial backing of the state, institutions like the NAPC become prominent cultural facilities. Perhaps they will not usher in ideological transformation by themselves. But they do help in small ways to re-fashion the way the Party presents the past (both the distant past and its own more immediate history) to the public.

Because of their limited accessibility to the general public, the current audience of the project also should be seen in a more limited scope—the Party’s internal ranks of cadres, SOE managers, and officials. Friends of mine who have parents working as government officials had heard about their visits to various branches not open to the general public. Given Xi’s concern about the Party losing its ideological discipline and warnings to not “forget the original intention” (不忘初心), the NAPC project’s first audience seems to be the Party’s own rank and file. But whether Party discipline or ideological commitment can really be bolstered by such a complex seems a bit of a lofty aspiration in an age of widely available media and alternative ideas.

Breslin, Shaun. “The “Two Integrations” And The (Increasing) Chineseness of Chinese Marxism” EH4S, (2024) https://eh4s.eu/publication/The-Two-Integrations-And-The-Increasing-Chineseness-of-Chinese-Marxism

Ho Kilpatrick, Ryan. Two Combines 两个结合 China Media Project (2023) https://chinamediaproject.org/the_ccp_dictionary/two-combines/

Guy, R. Kent. The Emperor’s Four Treasuries: Scholars and the State in the Late Chʻien-Lung Era. Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1987.

Johnson, Ian. Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2023.

This article is absolutely fascinating!!

wow beautiful structure if nothing else.